Sadao S. Munemori

Private First Class

Company A, 100th Infantry Battalion, 442d Regimental Combat Team, 92d Infantry Division

August 17, 1922 – April 5, 1945

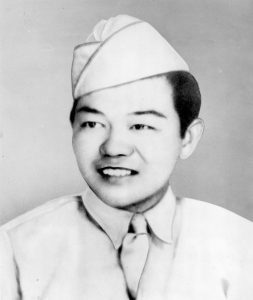

Pfc. Sadao Munemori U.S. Army

The metal clang of a German grenade against his helmet caught Pfc. Sadao Munemori’s attention. He was steps from safety in a shell crater high on the Apennine Mountains in Italy where two of his comrades awaited him. He watched as the grenade rolled toward his friends in the crater. Instead of diving toward safety, Munemori dived onto the grenade, placing his body between the men and the lethal explosion. As Munemori smothered the grenade, it detonated, killing him instantly, but the protection afforded by his sacrifice saved the other two Soldiers from serious injury. For his heroism and sacrifice on April 5, 1945, Munemori became the first Japanese American to earn the Medal of Honor. His choice exemplified the call to service and willingness to sacrifice that pervaded every member of the 442d Regimental Combat Team in World War II.

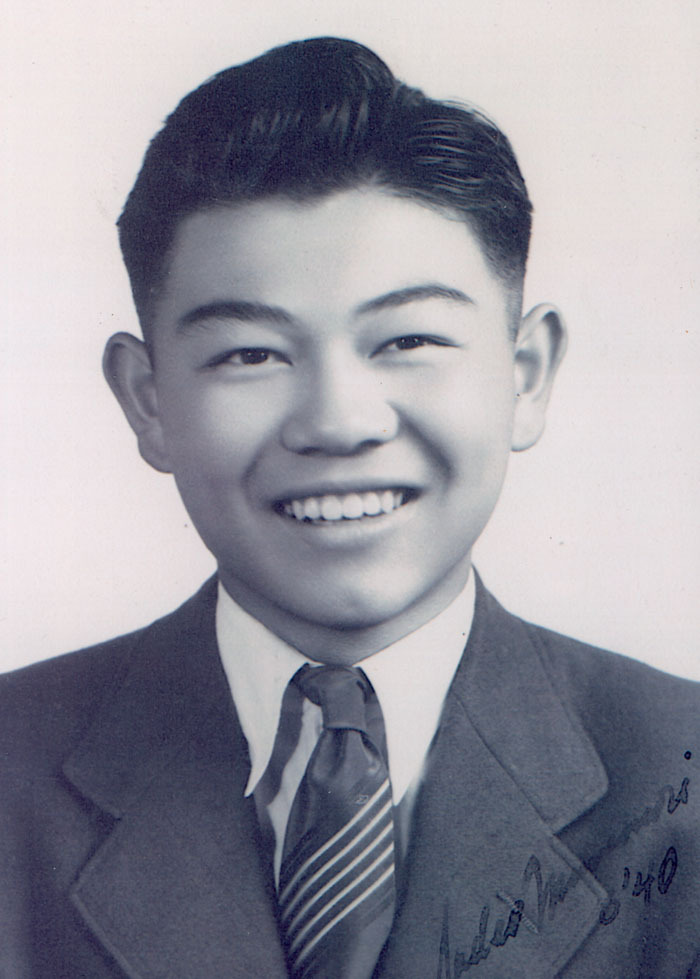

Sadao Munemori’s high school graduation portrait, June 1940. National Parks Service

Sadao S. Munemori was born on August 17, 1922, to parents Kametaro (father) and Nawa (mother) Munemori. Kametaro and Nawa were immigrants from Hiroshima, Japan who settled in Glendale, California, where Sadao attended Abraham Lincoln High School. Sadao was the fourth of five children, and spent his early years like many of his peers, with one exception: he was Japanese. Even before the Japanese attack on December 7, 1941, at Pearl Harbor, Japanese Americans faced segregation and racism throughout the United States. Munemori was once refused entry to a public pool alongside his friends because of his heritage, and he struggled to find work after he graduated high school in 1940.

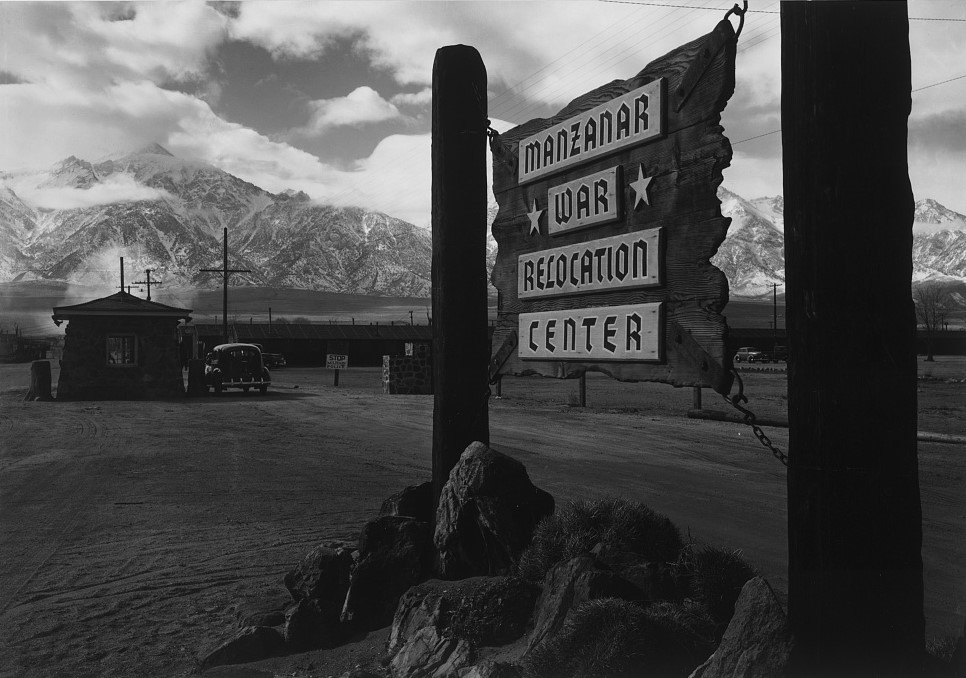

Seeking a better life for himself and his family after the passing of his father, Munemori volunteered for the U.S. Army in November 1941, as a language specialist. Munemori waited three months before the military approved his enlistment, formally entering into the Army on February 11, 1942. In the intervening months, Japanese Imperial Navy forces attacked Pearl Harbor and declared war on the United States. The surprise attack caused an uproar within the United States, and heightened anti-Japanese sentiment. Only a week after Munemori formally enlisted in February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt enacted Executive Order 9066, forcing Japanese Americans across the West into internment camps. Munemori’s family relocated to Manzanar, a camp high in the eastern Californian desert while Munemori himself went to military training.

Entrance sign at Manzanar War Relocation Center, 1943. Ansel Adams | Library of Congress

Owing in part to generalized animosity toward Japanese Americans, Munemori spent his first months in the Army doing menial labor, constructing barracks, and cleaning bedpans at military hospitals. Finally, in November 1942, Munemori attended the Military Intelligence Service Language School at Camp Savage, Minnesota. While Munemori was at Camp Savage, the Army began forming an all Nisei, or second generation Japanese American, combat unit named the 442d Regimental Combat Team (RCT). Munemori volunteered for the combat unit, instead of staying in school, despite the reduction in rank from technical sergeant to private that came with the reclassification.

Munemori visited his family at Manzanar in March 1943, before heading to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, for infantry training. Unbeknown to him, this would be the last time he saw his family. After training at Camp Shelby, Munemori shipped overseas to join the 442d as a member of Company A, 100th Infantry Battalion. Munemori joined the unit in 1944 as it fought in the Rome-Arno Campaign and the rescue of the “Lost Battalion” in the French Vosges Mountains. After nine months, the unit shipped south to Italy, where it joined the Allied effort in April 1945 to break through the Gothic Line, Germany’s last major defensive position in Italy, a maze of minefields, trenches, and barbed wire that stopped American and Allied attacks for months.

Allied commanders ordered Munemori’s unit to attack the Gothic Line along a steep mountain trail near the town of Seravezza, Italy. In the predawn darkness of April 5, Munemori and the rest of Company A climbed the mountain track toward the German position. At sunrise, the Americans attacked the German position with artillery, machine gun, and rifle fire. Company A initially made progress against the surprised Germans. However, German machine guns soon pinned down the company in a vicious crossfire. One gun wounded Munemori’s squad leader, leaving Munemori in charge of his small unit. Acting alone, Munemori charged a machine gun pit under heavy fire. Closing to within 20 meters, he tossed grenades into the German position until he knocked it out of action. He then repeated his gallant action against another enemy machine gun, using more grenades to destroy the position. Despite his brave actions to eliminate the lethal German fire, the rest of his company took too many casualties to continue the attack and began to withdraw.

Munemori, who was alone near the German line, sprinted across the battlefield back to his unit. He almost made it to the relative safety of a shell crater when a German soldier nearby threw a grenade in his direction. The grenade struck Munemori in the helmet and careened toward Munemori’s squadmates hiding in the crater. Without hesitation, Munemori sacrificed himself to save his comrades. Watching from the crater, Munemori’s squadmates witnessed his last act of selfless service. They saw him as he smothered the grenade with his body and rolled with it away from their position. Both men survived the ensuing explosion with light injuries, thanks only to Munemori.

Munemori’s selfless act took none of his peers by surprise. After the war, several of his friends told stories of “Spud,” as he liked to be called, and his attitude during the war. He was “friendly, outgoing, accepting,” and just as tough on arrival as the seasoned veterans of the 442d RCT wrote Stanley Izumigawa, one of Munemori’s Hawaiian friends “Spud” found especially endearing. Munemori dreamed of visiting his friends in Hawaii after the war. “All of us boys are already thinking of the future,” he wrote from France, adding that “the fellows want me to come to Hawaii and visit them for sure. That’s one thing that I’ll have to do when I return.” Sadly, Munemori never visited the island home of his closest friends. Instead, he chose to protect them, and ensure they themselves could return home.

Munemori’s unit, the 442d RCT became one of the most decorated regiments in the U.S. Army during World War II. However, owing to anti-Japanese sentiment within the military and across America, none of the 14,000 men who served in the unit during the war received a Medal of Honor. After the war ended, Munemori’s comrades and superiors began to aggressively campaign for him to receive the nation’s highest award for valor. On March 13, 1946, their efforts to recognize Munemori’s bravery came to fruition, when his mother, Nawa, received the 442d RCT’s first Medal of Honor on Sadao’s behalf. Over time, the Medal passed through generations of Munemori’s family. However, as those who knew Munemori aged, they sought to find a permanent home for his award. In 2020, Munemori’s family and closest friends entrusted the Medal to the National Museum of the United States Army, where it remains on display to this day.

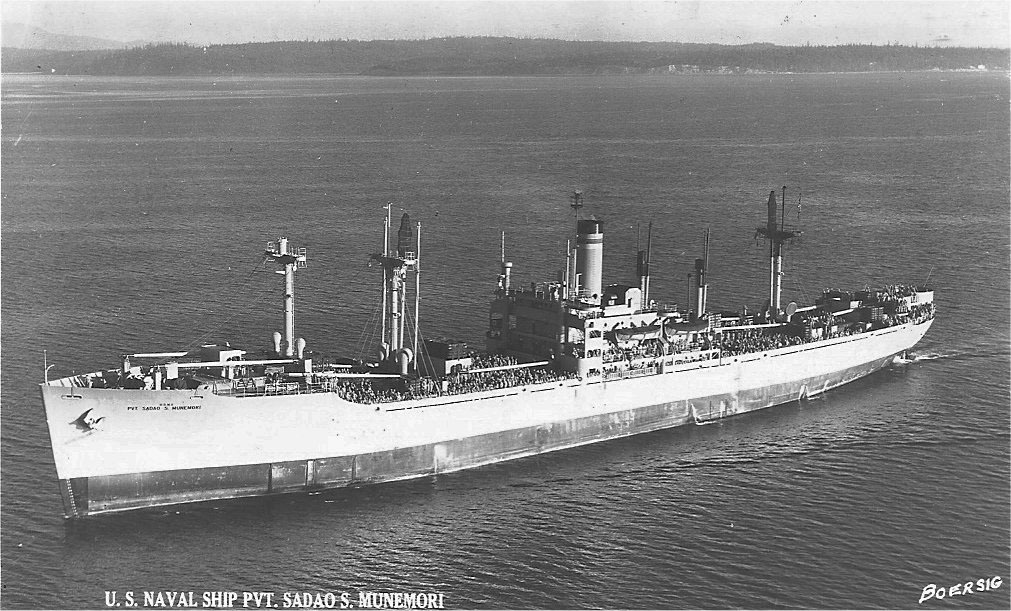

USNS Pvt. Sadao S. Munemori (T-AP-190), circa 1950. U.S. Navy

Numerous places and organizations recognize Munemori’s sacrifice and bravery. In 1947, the U.S. Navy renamed the 10,000 ton troop ship SS Wilson Victory to the USAT Pvt. Sadao S. Munemori (later USNS Pvt. Sadao S. Munemori). The U.S. Army Reserve Center in West Los Angeles, near Munemori’s home, is named in his honor. In 2000, the city of Pietrasanta, Italy, dedicated a sculpture in Munemori’s likeness as a token of gratitude for the entire 442d’s actions in liberating Italy.

Jacob M. Henry

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Sources

Congressional Medal of Honor Society. “Sadao S. Munemori.” Accessed April 7, 2022. https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/sadao-s-munemori.

Lange, Katie. “Medal of Honor Monday: Army Pfc. Sadao Munemori.” U.S. Department of Defense. May 3, 2021. https://www.defense.gov/News/Feature-Stories/story/Article/2586993/medal-of-honor-monday-army-pfc-sadao-munemori/.

Gentry, Connie. “Private First Class Sadao S. Munemori’s Medal of Honor.” The National WWII Museum. May 3, 2021. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/sadao-s-munemori-medal-of-honor.

Niiya, Brian. “Sadao Munemori.” Densho Encyclopedia. Last modified July 2, 2020. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Sadao%20Munemori/.

Tamashiro, Ben H. “From Pearl Harbor to Po.” University of Hawaii. March 15, 1985. http://nisei.hawaii.edu/object/io_1149130450078.html.