George Washington

General of the Armies

Continental Army

February 22, 1732 – December 14, 1799

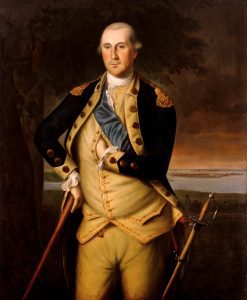

George Washington by Charles Willson Peale, 1776. White House Historical Foundation.

Few figures loom as large in American military history as George Washington. In many ways, he is viewed almost as a mythical figure and is typically remembered for his momentous achievements. He led the Continental Army to victory in the Revolutionary War, helped create the U.S. Constitution, and served as the first president of the United States. In particular, his superb leadership qualities allowed him to succeed throughout his life. Though not without faults, he established a precedent of selfless service and moral integrity in the American armed forces, a legacy that lives on in the nation he helped create.

Born on February 22, 1732, to Augustine and Mary Ball Washington, the future president grew up in Virginia. His father, a justice of the peace, died in 1743, and Washington inherited part of his estate at Ferry Farm near Fredericksburg. Born into moderate wealth, Washington did not attend school but received a robust education in mathematics and land surveying. He began working as a surveyor in 1748 and completed several expeditions to the Shenandoah Valley. By the age of 20, Washington was a socially-connected, well-educated, wealthy landowner. Yet, Washington desired military service and received a commission in the Virginia Militia in 1752.

Washington, then a major, inadvertently started the French and Indian War in 1754 when his forces attacked and killed a French officer in a scouting party in the Ohio River Valley. French and Native American forces retaliated, defeating Washington’s militia force. The following year, Washington fought at the disastrous Battle of Monongahela on July 9, 1755, where the French and their Indian allies routed a large British and militia force. He continued to serve in the war, leading provincial units until he resigned in 1758. Though the British won the war, Washington’s reputation was far from certain. British leadership regarded him as a poor commander, while colonists viewed him as a hero for his bravery and steady leadership in battle.

After the war, he returned to Mount Vernon, which he would inherit from his brother Lawrence in 1761. He wished to make the farm profitable and spent considerable money to expand the property. Using the labor of over one hundred enslaved individuals, Washington successfully developed Mount Vernon into a prosperous plantation. In 1758, he was elected to a seat in the Virginia legislature. The following year, he married Martha Dandridge Custis, a wealthy widow. She and her two young children joined Washington at Mount Vernon. As the years went on, Washington grew increasingly interested in politics. By 1771, Washington openly criticized the British for what he viewed as oppressive tax policies towards the colonies. He was elected by the Virginia legislature to represent the colony at the First Continental Congress in 1774. After the eruption of open conflict in Massachusetts in April 1775, Washington attended the Second Continental Congress. On June 14th, Congress resolved to create a Continental Army. The following day, Washington was selected as the new army’s commander-in-chief. His personal integrity, military experience, and hero status all contributed to his selection. In many ways, he was viewed as the only man who could do the job.

On July 2, 1775, Washington arrived outside Boston to take command of the forces gathering there and create a regular army out of a ragtag band of poorly equipped militiamen and volunteers. Washington rapidly organized the Continental Army and selected several officers from the ranks, such as Maj. Gen. Henry Knox. Under Washington’s direction, Knox daringly moved 59 cannons over 300 miles from Fort Ticonderoga, New York, to Dorchester Heights outside of Boston. The plan worked and the British left Boston in March 1776. Though he had won his first major confrontation of the war, Washington and the Continental Army’s success was short-lived. Attempting to capture New York, British general Sir William Howe decimated the Continental Army in a series of battles. By the end of 1776, Washington’s Army was demoralized and shaken. Ninety percent of the troops he had commanded in Boston were either killed, wounded, captured, or had left the Army. With morale low, Washington launched a surprise attack on December 26, 1776 against the British allied Hessian forces camped in New Jersey at Trenton and Princeton. Caught by surprise, the Americans routed the Hessian forces and Washington achieved an important victory for his Army.

Over the course of the next few years, Washington enjoyed few battlefield successes as he was regularly defeated by superior British forces. Yet, Washington’s stalwart leadership, integrity, and dignity held the Army together, presenting a credible threat to the British. After Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates’ army defeated the British at the battles of Saratoga in September and October 1777, France entered the war and allied with the Americans in 1778. This provided Washington with the weapons, supplies, and reinforcements he needed to achieve a decisive victory.

After a large French force commanded by the Comte de Rochambeau joined Washington’s forces in 1781, the two generals planned a pivotal strike. Though Washington favored attacking New York, Rochambeau and the French believed the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia to be the best target to isolate and capture an entire British army. After a French fleet commanded by the Comte de Grasse successfully blockaded the Chesapeake Bay, the Franco-American forces besieged a large British army at Yorktown, Virginia. The British surrendered on October 19, 1781, effectively ensuring victory in war and independence.

Near the end of war, Washington successfully stopped a coup attempt by Continental Army officers at Newburgh, New York, in March 1783. Yet again, Washington’s personal qualities and leadership proved invaluable. On September 3, 1783, the Revolutionary War officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. Some believed Washington might not resign his commission and attempt to seize power, as he was extremely popular with the troops and the public. However, Washington resigned his commission and returned to Mount Vernon, bowing to Congress in a short ceremony on December 23, 1783, at Annapolis, Maryland. For this act alone, King George III called Washington, “the greatest man in the world.”

Initially, Washington intended to enjoy his retirement from public service, content to spend his life as a farmer at Mount Vernon. However, his retirement was interrupted when he was once again called on to serve his country. Washington was a unanimous choice to head the Constitutional Convention in 1787. His stalwart leadership, hero status, and dignified manner made him perhaps the only person capable of leading the assembly. He worked with the delegates for over a year to create and ratify the Constitution. Washington continued to lead and was unanimously elected the first President of the United States.

Washington reluctantly accepted a position of power once again, serving two full terms as president. His qualities as a natural and dignified leader made him an ideal choice for the job. Working closely with Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, who had served under Washington in the Revolutionary War, Washington created an energetic and centralized federal government, setting a precedent for the new American experiment. He helped establish a national bank, suppressed the Whiskey Rebellion, and established a trade relationship with Great Britain. After eight years in office, Washington again willingly stepped away from power, establishing the precedent of American presidents only serving two terms. He penned an emotional farewell address in 1796, where he warned against the dangers of political parties, foreign influence, and valuing a single state over the entire nation. He retired to Mount Vernon in 1797.

Washington devoted himself to improving Mount Vernon in his retirement. On December 12, 1799, he became ill after riding his horse through rain and sleet. His condition rapidly worsened and he died on December 14, 1799. At his funeral, Maj. Gen. Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee stated that Washington was, “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” These words accurately summarize Washington’s legacy. He was first in war as the commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, leading the charge for American independence. He was first in peace as a farmer, a husband, and the first President of the United States. And he was first in the hearts of his countrymen as a beloved hero for all Americans. His superb leadership abilities and humble example of giving up power set a precedent for Army leadership that continues to this day.

A.J. Orlikoff

Lead Education Specialist

Sources

“George Washington: The Father of the Nation.” American Battlefield Trust. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/george-washington.

Chernow, Ron. “George Washington: The Reluctant President.” Smithsonian Magazine, February 2011. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/george-washington-the-reluctant-president-49492/.

Ellis, Joseph J. “Washington Takes Charge.” Smithsonian Magazine, January 2005. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/washington-takes-charge-107060488.

“Biography of George Washington.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/biography/.

Kladky, William P. “Continental Army.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/continental-army.

Knott, Stephen. “George Washington: Life before the Presidency.” Miller Center. Accessed May 3, 2021. https://millercenter.org/president/washington/life-before-the-presidency.

Additional Resources

Chernow, Ron. Washington: A Life. New York: Penguin Press, 2009.