Far from the heady days of Independence in the summer of 1776, December found George Washington’s Continental Army worn down and nearing defeat. Knowing that bold action was needed to keep the cause of independence alive, Washington sought an opportunity. A raid, giving Soldiers a chance to go on the attack, could reinvigorate his army and the public, and force the British onto the defensive. The determination of the Soldiers ensured the cause of American Independence remained a real possibility through the trying winter months.

“I Think the Game is Pretty Near Up.”

Entering winter of 1776, the optimism which surrounded summer’s Declaration of Independence had largely disappeared. Defeat at Long Island, indecisive battles at Harlem Heights and White Plains, and the loss of Forts Washington and Lee drove the Continental Army out of New York. Alongside these disastrous defeats, Washington’s army melted away. Militia left by entire companies when their periods of service expired. Casualties, prisoners of war, and disease further reduced available Soldiers. Only British Maj. Gen. William Howe’s delay in attacking Washington’s retreating force saved the Continental Army. Granted additional time without pursuit, Washington moved across the Delaware River into Pennsylvania on December 7 and 8. Without a clear opportunity for attack, and hoping that expiring enlistments would scatter Washington’s army, Howe stopped his pursuit and formed cantonments, or temporary military camps, for the winter.

Washington knew that he needed to raise morale. Congress was losing hope, as was his army and fellow patriots. The Continental Congress, afraid the British would seize Philadelphia before Christmas, fled to Baltimore. Washington thought the British would wait until the Delaware River froze over, then march across to destroy the Continental Army. On December 18, Washington wrote to his brother: “If every nerve is not strained to recruit the new army with all possible expedition, I think the game is pretty nearly up . . .You can form no idea of the perplexity of my situation. No man, I believe, ever had a greater choice of difficulties, and less means to extricate himself from them.”

An Opportunity Arises

Dire as the situation may have seemed in mid-December, the situation began to improve for the embattled general. Washington’s force increased as scattered regular army units returned and militia trickled into his encampment. By the end of December 1776, Washington had assembled a small but capable force of veteran regiments and experienced militia. If he was to use this rejuvenated army, he would have to do so before the enlistments expired on December 31. Washington planned to attack garrisons along the Delaware River early on December 26, when the enemy might be less alert.

Washington’s chosen target was more vulnerable than he realized. Howe’s outposts lacked coordination due to a belief that Washington’s army would not cross the river and attack during the winter. The British stationed Hessian battalions, hired troops from several German principalities, few of whom spoke English, in the towns closest to Washington and his army. Trenton, New Jersey, in particular became a focal point for patriot violence. Local militias, angered by Hessian attacks on their land and families, harassed the garrison every night between December 22 and 25. This constant action and the need to arrange lengthy patrols to counter attacks had worn down the outpost of around 1,500. A Hessian officer wrote in complaint: “We have not slept one night in peace since we came to this place. The troops have lain on their arms every night and we can endure it no longer.” When a winter storm blew in on December 25, Hessian officers saw a chance to allow the garrison to rest and recover. A harassing attack early that night convinced the Hessian commander, Col. Johann Rall, that his soldiers need not fear an attack until the next night. While Washington hoped to catch the defenders after a night of celebrating, he would instead find them worn down by days of stress and alerts.

An Audacious Plan

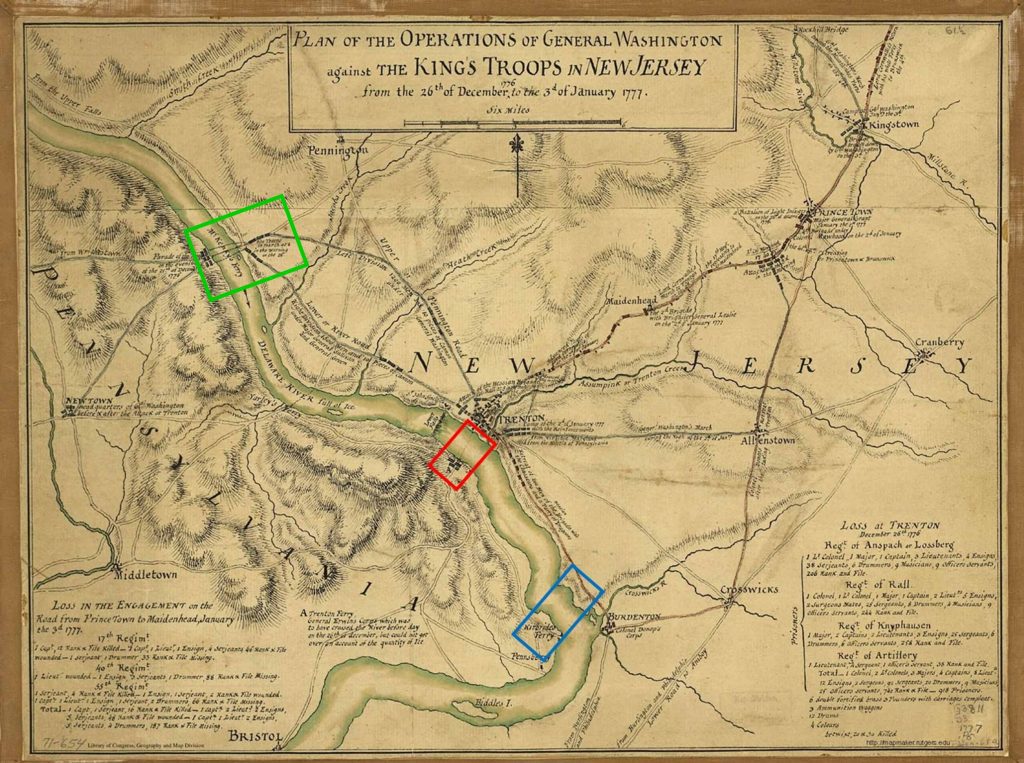

Washington’s Plan, with Ewing’s Crossing (Red) and Cadwalader’s Crossing (Blue) south of Washington’s Crossing (Green). Library of Congress

Washington planned for three American forces to cross the Delaware River and conduct raids on the outposts at Trenton and Bordentown, New Jersey. Around 2,400 Soldiers under Washington’s personal command would cross the river and proceed in two columns, converging on Trenton from high ground in the early morning of December 26. A second force under Col. John Cadwalader would attack the Hessian garrison at Bordentown to fix them in place and prevent them from reinforcing the Hessian forces in Trenton. A third force under Brig. Gen. James Ewing would block a bridge at Assunpink Creek and complete the isolation of Trenton for Washington’s raid. Col. Henry Knox would command his artillery to support Washington’s assault on Trenton and would also command the crossing operation. Washington issued “Victory or Death!” as the password and officers emphasized the need for absolute silence, obedience, and order to each Soldier. Every Soldier would carry three days of rations and forty rounds of ammunition, while all officers set their watches by Washington’s to ensure synchronized execution of this raid.

Early Setbacks and Perseverance

Washington made a detailed plan but the environment undid much of it. Despite being only 300 yards wide at the point of the crossing, the Delaware River presented a formidable challenge. Even with the help of experienced watermen, navigating a river clogged with jagged cakes of ice was a difficult task. The weather made it harder: by the time most of the Soldiers reached the launching point for the boats, a cold drizzle had turned into a driving rain. By 11 p.m., while the boats were crossing the river, a howling nor’easter made the miserable crossing even worse. One Soldier recorded that “it blew a perfect hurricane” as snow and sleet lashed Washington’s army. No one died during the crossing, though many Soldiers could not swim and several fell overboard. Perhaps more impressively, all the terrified horses and the heavy artillery pieces arrived ready for action.

Washington had anticipated getting his troops across before midnight, so he could attack what he assumed to be drowsy Hessians. But storm and limited visibility made rapid movement impossible. The last Soldier reached the eastern bank at 3 a.m., having braved blinding snow, piercing wind, and icy waters under Knox’s booming direction. It was 4 a.m. on December 26 before Washington’s Soldiers were ready to start on their march toward Trenton. With every delay Washington’s fears that his army would be caught in the open increased. Delays and conditions at other crossing points also meant that the groups under Cadwalader and Ewing failed to make the crossing. Washington would not have his blocking and fixing elements in place and would only have 2,400 Soldiers instead of 5,000. If something went wrong, the army would have no reserves. Washington later wrote, when remembering this fateful moment, “…As I was certain there was no making a retreat without being discovered and harassed on repassing the River, I determined to push on at all Events.” Four hours behind schedule, the ten-mile march (a welcome relief to Soldiers because movement meant finally warming up after the crossing) to Trenton began. The wet conditions continued along the march and into the attack, with dry gun powder at a premium.

“Victory or Death” General Washington leads his army toward Trenton on the morning of December 26, 1776. Don Troiani

The Raid

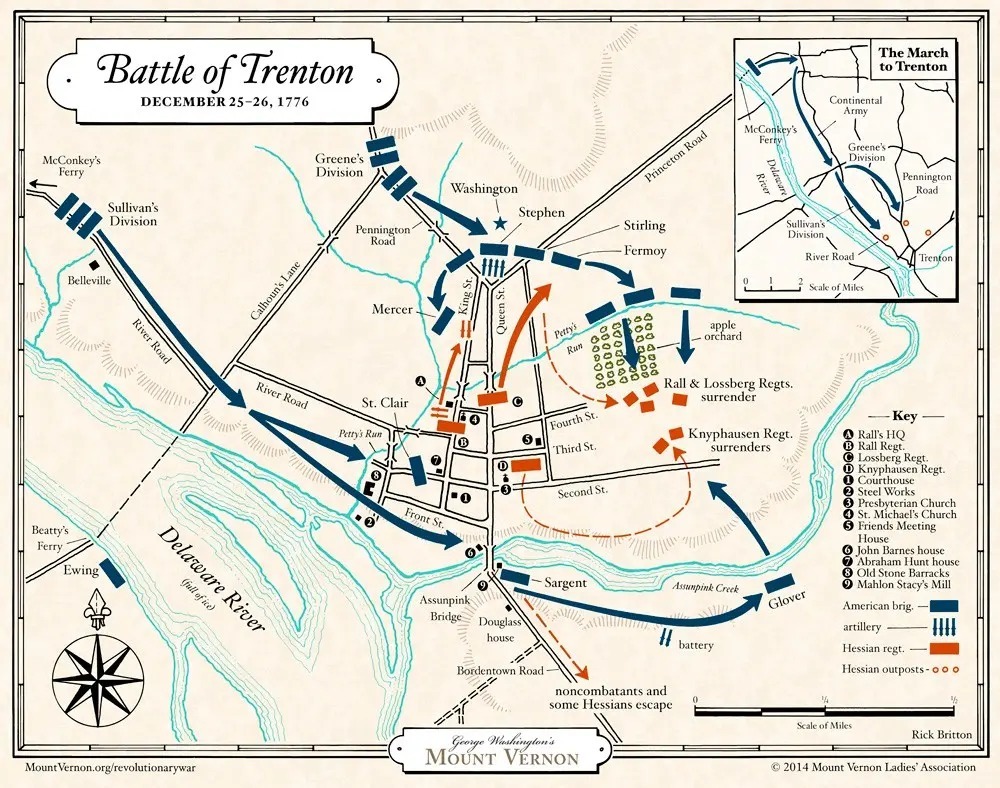

As he approached the town, Washington divided his men. He sent flanking columns under Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene and Maj. Gen. John Sullivan north and south of Trenton. Knox’s 18 cannons established positions to fire onto the main roads and center of the town. Greene further divided his forces to encircle the town: New Englanders and Marylanders on the right, Pennsylvanians on the left, and Virginians backed by Delaware infantry in the center. Scouts brought word of Hessian outposts, which Washington then moved to destroy. Washington’s forces overran the Hessian outposts on the edge of town, but not before the Hessians raised the alarm. The Hessian officers mobilized three regiments with artillery support. Knox’s artillery entered the action, firing down the central street with solid shot and canister (with effects like a giant shotgun) to disrupt the assembling Hessian regiments. Col. Rall attempted to form a line of defense on King and Queen Streets with two regiments and the Knyphausen battery. As Rall’s artillery entered the action, Knox’s guns overwhelmed the Hessians and forced supporting infantry to withdraw.

Washington’s Raid in Action. Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. Map created by Rick Britton.

Washington’s Raid in Action. Courtesy of Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. Map created by Rick Britton.

With Hessian cannons fighting a delaying action in the town, Rall attempted to attack up onto the high ground on Washington’s left flank. The Continental Soldiers on the eastern flank, reacting to the change, moved to establish clear fields of fire along Rall’s advance. Continuing Rall’s attack would have been reckless: instead, he attacked back into the town towards his artillery. Anticipating this, Washington’s Soldiers established interlocking artillery and infantry fields of fire from three sides. The Continental Army could fire from houses where they had concealment and the chance to dry their powder. While the Hessian infantry managed to reach their artillery, a furious attack by Virginia infantry and New England artillerymen (without their guns) drove the Hessians back and turned the artillery on its owners at close range. American infantry, seeking to further disrupt the Hessian command structure, began targeting officers. This stalled the counter-attack by removing several company commanders and, finally, Rall. The surviving Hessians, their powder damp, deprived of artillery support, and their commander dying, surrendered or fled.

The Aftermath

The Hessians lost 22 men with another 86 receiving wounds. Washington’s forces also captured close to 900 enemy troops. Four hundred Hessians escaped because Washington’s blocking force was stranded on the other side of the Delaware. In contrast, the Americans suffered only five casualties. Among them was Lt. James Monroe, future president of the United States, who nearly died leading the final attack to seize the Hessian artillery. Now, whatever Howe’s plans for the winter may have been, it shifted to defending the gains made during the New York campaign. Washington proved his competence after previous humiliations and prompted re-enlistments and new enlistments to preserve his force. Almost more importantly, his Soldiers had proved they could stand toe to toe with disciplined European troops. The Continental Army also seized much-needed supplies, including cannons and 1,200 muskets. While the operational gains were important, the strategic impact far outweighed the real gains. Washington’s late Christmas gift captured popular imagination and new support at a key point in the War for Independence.

Jonathan Curran

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Sources

Ferling, John. Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Ferris, Frederick L. “The Two Battles of Trenton.” In A History of Trenton, 1679-1929: Two Hundred And Fifty Years of A Notable Town With Links In Four Centuries, edited by Edwin Robert Walker and Clayton L. Traver, Chapter 3. Trenton Historical Society, 2012. https://www.trentonhistory.org/His/battles.html.

Fischer, David Hackett. Washington’s Crossing. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Higginbotham, Don. The War of American Independence: Military Attitudes, Policies, and Practice, 1763-1789. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1971.

Savas, Theodore P. and J. David Dameron. A Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution. New York: Savas Beatie LLC, 2006.

Stryker, William S. The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, 2001 ed. Trenton: The Old Barracks Association, 2001.