Photograph of the attack taken from a Japanese plane after a torpedo hit USS West Virginia. Naval History and Heritage Command

On the morning of December 7, 1941, servicemen stationed at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, attended to their daily duties. Sailor Cecil Camp was beginning his Sunday as usual, remembering, “I had relieved the watch in the port engine room [of the USS Utah]. I had been on watch about 20 minutes when the first torpedo hit the ship on the port side.” At 7:55 a.m. HST, hundreds of Japanese planes released bombs and torpedoes onto the Army and Navy facilities at Pearl Harbor. Unsure of what was going on, Pvt. Robert Kinzler, a Soldier stationed at nearby Schofield Barracks, headed to his battle station. Along the way, he witnessed, “huge columns of thick black smoke and deep orange flames rising up from Pearl Harbor.” While historians often highlight the Navy’s role in the attack, Army forces at Pearl Harbor were also involved. Their sacrifices and bravery marked the beginning of the eventual defeat of the Japanese during World War II. A surprise strike of this magnitude was previously unthinkable. The attack on Pearl Harbor not only inducted the United States into World War II, but also altered the cultural attitude on war in the United States for decades to come.

Background on Attack

World War II began in Europe and Asia in the late 1930s, but American leaders, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt, chose to stay out of the conflict. In the years leading up to 1941, Americans were deeply divided over their involvement in the war. Isolationists hoped the United States would remain neutral, while interventionists wanted to enter the war. The United States remained neutral for most of 1941. However, polls indicated that Americans were increasingly concerned about the success of the Axis powers—Germany, Italy, and Japan—in 1940 and 1941.

While the United States did not formally take a side in the war in the 1930s, tensions between the United States and Japan grew. They began simmering with the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 when Japanese forces launched an invasion of China. The United States condemned this act of war by passing trade sanctions and an embargo against Japan. These actions marked a significant transition from the open trade relationship Japan and the United States previously enjoyed. The oil embargo was particularly damaging to the Japanese, who required imported oil and other supplies to continue expanding their empire. This pushed the Japanese to consider all options to obtain the resources they needed.

Japanese military officers discussed targeting Pearl Harbor as early as January 1941. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the commander-in-chief of the Japanese Combined Fleet, led the planning. American codebreakers deciphered Japanese communications about an attack on Pearl Harbor, but Army and Navy leaders deemed the threats unlikely. Positioned on Oahu, Hawaii, Pearl Harbor served as the main base for the American Naval Fleet in the Pacific Ocean. It also hosted several Army airfields and Schofield Barracks, headquarters of the 25th Infantry Division, where 35,000 Soldiers were stationed. In fact, more Soldiers than sailors were present on Oahu the day of the attack.

Despite intelligence indicating a Japanese military interest in Pearl Harbor, the post’s location over 4,000 miles away from Japan inspired a false sense of security. Much closer to Japan was the Philippine Commonwealth, which American military leaders such as Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall predicted would be a more likely target. However, a “war warning” was still issued to Army and Navy leadership on the island. Lt. Gen. Walter Short, commanding general of Hawaiian military installations, was more concerned with the threat of espionage. At his order, Hawaii’s threat level was downgraded to an alert against sabotage.

Yamamoto finalized plans to attack Pearl Harbor in July 1941. Japanese leadership hoped this preventive action would end the threat of the U.S. military in the Pacific, allowing the Japanese to expand their empire without interference. On the morning of December 7, U.S. intelligence intercepted a message from Japanese forces indicating action would be taken. They delivered the message to Washington four hours prior to the attack. However, delays in transmission caused a late delivery to Pearl Harbor—not until almost 3 p.m. HST, hours after the attack.

The Attack

The attack on Pearl Harbor lasted approximately an hour and a half and consisted of two waves of enemy attackers. Four hundred and eight Japanese aircraft launched from six aircraft carriers operating two hundred miles north of Oahu in the first wave. An Army SCR-270 radar installation on the northern tip of Oahu first detected the threat. Privates George Elliot Jr. and Joseph Lockard reported the sighting, but the lieutenant on duty assumed the incoming planes were a scheduled delivery.

While approaching Oahu, Japanese forces shot down American planes as they attempted to send warning signals. This resulted in unclear messages to headquarters. Reaching the harbor, Japanese torpedo bombers targeted the valuable American battleships. Shortly after the attack began, a Japanese high altitude bomber hit the USS Arizona, causing its forward ammunition magazine to explode. Arizona sank rapidly with over 1,000 men trapped inside, contributing to nearly half the total casualties from the attack. Bombs, torpedoes, and machine gun fire struck other battleships surrounding Arizona.

USS Arizona sinking after impact. National Archives

Japanese dive bombers and fighters reached Hickam Field (now Hickam Air Force Base) and Wheeler Field (now Wheeler Army Airfield), the main bases of the U.S. Army Air Force, around 8 a.m. HST. Many servicemen awoke to exploding bombs and the announcement, “Air raid Pearl Harbor. This is not [sic] drill.” At the time of the attack, the Army’s nearby anti-aircraft guns were nonfunctional, and batteries and ammunition were not in use. Two Army Air Force pilots, 2d Lt. Kenneth Taylor and 2d Lt. George Welch, awoke to the sounds of the Japanese attack. Without orders, they rushed to the airfield to board their Curtiss P-40 Tomahawks. Taylor and Welch launched offensive strikes twice, landing only to reload. Welch managed to shoot down four Japanese planes; Taylor shot down two, in the process taking fire that struck his arm and leg. As two of only five U.S. pilots that managed air defense on December 7, Taylor and Welch earned Distinguished Service Crosses, and Taylor earned a Purple Heart.

One hundred and seventy-one additional Japanese planes launched in the second wave, starting at 8:55 a.m. HST. Battleships and destroyers sustained more damage, and several bombers targeted the military airfields. The Japanese Imperial Navy also stationed submarines surrounding Oahu, meant to target ships escaping the barrage. The Japanese attack by sea was far less successful than their aerial assault, however. The sole captured enemy serviceman piloted a submarine that washed ashore.

By the end of the attack, 347 American aircraft were destroyed or damaged. All eight battleships anchored in Pearl Harbor were either sunk or damaged, though six were eventually salvaged. Ship repair yards and ammunition storage facilities were notably unharmed, allowing for a swift rebuilding process to begin soon after. In all, 2,335 Americans died in the attack. Almost 70 of these deaths were civilians, notably members of the Honolulu Fire Department who responded to Hickam Field and the passengers of three civilian planes.

The wreckage of USS Downes with the capsized USS Cassin leaning against it. The battleship USS Pennsylvania sits behind. In the background, smoke billows from the USS Arizona. National Archives

Aftermath of Attack

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan formally declared war on the United States. On December 8, President Roosevelt addressed a joint session of the U.S. Congress, urging them to declare war on Japan. Within the hour, the bill passed. The United States declared war on Japan, soon followed by a declaration of war by Germany and Italy.

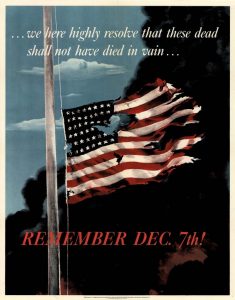

Despite the success of the surprise attack, the Japanese objectives were unmet. Instead of scaring Americans away from war with Japan, the attack angered them. More importantly, it weakened American attachment to isolationism that previously halted their participation. After Roosevelt’s plea for justice, 388 of 389 members of Congress voted to declare war, the one “nay” vote coming from a staunch pacifist. Over the next four years of warfare, the American military played a key role in the defeat of Axis Powers in World War II. Japanese Admiral Hara Tadaichi later summarized the result of the attack on Pearl Harbor as, “We won a great tactical victory at Pearl Harbor and thereby lost the war.”

One of many pieces of propaganda garnering support for the war effort after the attack. Allen Saalburg | Public Domain

The attack on Pearl Harbor had deep implications for the Japanese American community. A nation traumatized by the surprise attack scapegoated many minority communities. In February 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, approving the forced incarceration of Japanese Americans in internment camps. Soldiers of Japanese descent faced intense scrutiny, despite their commitment to defend their country. Several second-generation Japanese Americans, also known as Nisei, were serving in the Army and Hawaiian National Guard in December 1941. Sgt. Gary Uchida, Sgt. Shigeru Inouye, and 2d Lt. Takeichi Miyashiro were each present in Pearl Harbor on the day of the attack. All three men later served in World War II in the 100th Infantry Battalion. The majority-Nisei battalion chose the motto “Remember Pearl Harbor” and is one of the most highly decorated units in Army history.

Soon after the attack, the Roosevelt administration appointed the Roberts Commission to investigate the attack. Among the 127 subjects interviewed was General Marshall. Marshall was angry, especially about Hawaii’s lack of available defenses during the attack. He stated that though he did not deem Pearl Harbor to be in imminent danger, he still expected it to be prepared for a surprise attack. While testifying before Congress, Marshall stated, “I never could grasp what had happened between the period when so much was said [in Hawaii] about air attack, the necessity for antiaircraft, the necessity for planes for reconnaissance, the necessity for attack planes for defense and the other requirements which anticipated very definitely and affirmatively an air attack—I could never understand why suddenly it became a side issue.” Marshall, however, was not blameless. He notably failed to follow up with Pearl Harbor leadership after forwarding the vital message to Hawaii the morning of December 7.

While no party was solely to blame for the lack of preparation for the attack, Lt. Gen. Short and Adm. Husband E. Kimmel faced the consequences. Both men were relieved of their commands and retired soon after at lower ranks. It was not until long after their deaths that public opinion toward the men shifted. Adm. William Harrison Standley, member of the Roberts Commission, acknowledged decades later that, “These two officers were martyred.” In 1999, the U.S. Senate exonerated the men following a Department of Defense investigation. The report noted that the Japanese attack was “not a result of a dereliction of duty,” as had been previously stated by the Commission’s findings.

In his famous speech, Roosevelt vowed the attack would be “a date which will live in infamy.” His prediction was correct in more ways than one. Not only has the solemnity of the day lived on, though, but so too have the acts of heroism committed in response. In 1994, Congress named December 7 National Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day. Each year, memorials across the country honor the servicemen who lost their lives and served with honor that day.

Delaney Brewer

Co-lead Education Specialist

Sources

“Cecil Camp.” National Parks Service. Last modified July 18, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/perl/learn/historyculture/cecil-camp.htm.

Matloff, Maurice. “World War II: The Defensive Phase.” In American Military History. Washington, DC: Center for Military History, 1989. https://history.army.mil/books/AMH/AMH-20.htm.

Correll, John T. “Caught on the Ground.” Air Force Magazine, December 1, 2007. https://www.airforcemag.com/article/1207ground/.

Danforth, Bruce. “Why Japan Attacked Pearl Harbor.” Pearl Harbor. August 27, 2015. https://pearlharbor.org/why-japan-attacked-pearl-harbor/.

Dupuy, Trevor N. “Pearl Harbor: Who Blundered?” American Heritage 13, no. 2 (February 1962). https://www.americanheritage.com/pearl-harbor-who-blundered#20.

Filseth, Trevor. “The Forgotten Reason Japan Attacked Pearl Harbor.” The National Interest, The Buzz (blog), December 9, 2020. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/forgotten-reason-japan-attacked-pearl-harbor-174121?page=0%2C1.

Gentry, Connie. “Going for Broke: The 100th Infantry Battalion.” The National World War II Museum. August 1, 2020. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/japanese-american-100th-infantry-battalion.

Hardaway, Robert M. III. “The Army at Pearl Harbor.” Journal of the American College of Surgeons 190, no. 5 (May 1, 2000). https://www.journalacs.org/article/S1072-7515(99)00242-2/fulltext.

Haufler, Hervie. Codebreakers’ Victory: How the Allied Cryptographers Won World War II. New York, NY: Open Road Integrated Media, 2014.

“How Many People Died at Pearl Harbor during the Attack?” Pearl Harbor. Accessed December 1, 2021. https://pearlharbor.org/faqs/how-many-people-died-at-pearl-harbor-during-the-attack/

“Marshall and Pearl Harbor Hearings.” George C. Marshall Foundation, January 29, 2016. https://www.marshallfoundation.org/blog/marshall-and-pearl-harbor-hearings/.

Miles, Sherman. “Pearl Harbor in Retrospect.” Atlantic, July 1948. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1948/07/pearl-harbor-in-retrospect/305485/.

“A Pearl Harbor Timeline.” NPR, December 7, 2004. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4206060.

Pruitt, Sarah. “Heroes of Pearl Harbor: George Welch and Kenneth Taylor.” History.com. November 28, 2016. https://www.history.com/news/heroes-of-pearl-harbor-george-welch-and-kenneth-taylor.

“Robert Kinzler.” National Parks Service. Last modified July 19, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/perl/learn/historyculture/robert-kinzler.htm.

Shenon, Philip. “Senate Clears 2 Pearl Harbor ‘Scapegoats’.” New York Times, May 26, 1999, sec. A. https://www.nytimes.com/1999/05/26/us/senate-clears-2-pearl-harbor-scapegoats.html.

Twomey, Steve. “How (Almost) Everyone Failed to Prepare for Pearl Harbor.” Smithsonian Magazine, December 2016. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/how-almost-everyone-failed-prepare-pearl-harbor-1-180961144/.

Worrall, Simon. “How Racism, Arrogance, and Incompetence Led to Pearl Harbor.” National Geographic, December 4, 2016. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/countdown-pearl-harbor-attack-twomey-anniversary.

Wueschner, Silvano A. “75th Anniversary: Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941.” Maxwell Air Force Base, December 6, 2016. https://www.maxwell.af.mil/News/Features/Display/Article/1021790/75th-anniversary-pearl-harbor-dec-7-1941/.

Additional Resources

Chappell, Bill. “Pearl Harbor 75 Years Later: U.S. Recalls A Shocking Attack.” NPR, December 7, 2016. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/12/07/504733373/pearl-harbor-75-years-later-u-s-recalls-a-shocking-attack.

“The Attack on Pearl Harbor.” Iowa PBS. Accessed December 1, 2021. Video, 1:58. https://www.iowapbs.org/iowapathways/artifact/gunners-mate-paul-aschbrenners-first-hand-account-attack-pearl-harbor.

Gallicchio, Marc. Unconditional: The Japanese Surrender in World War II. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Twomey, Steve. Countdown to Pearl Harbor: The Twelve Days to the Attack. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2017.