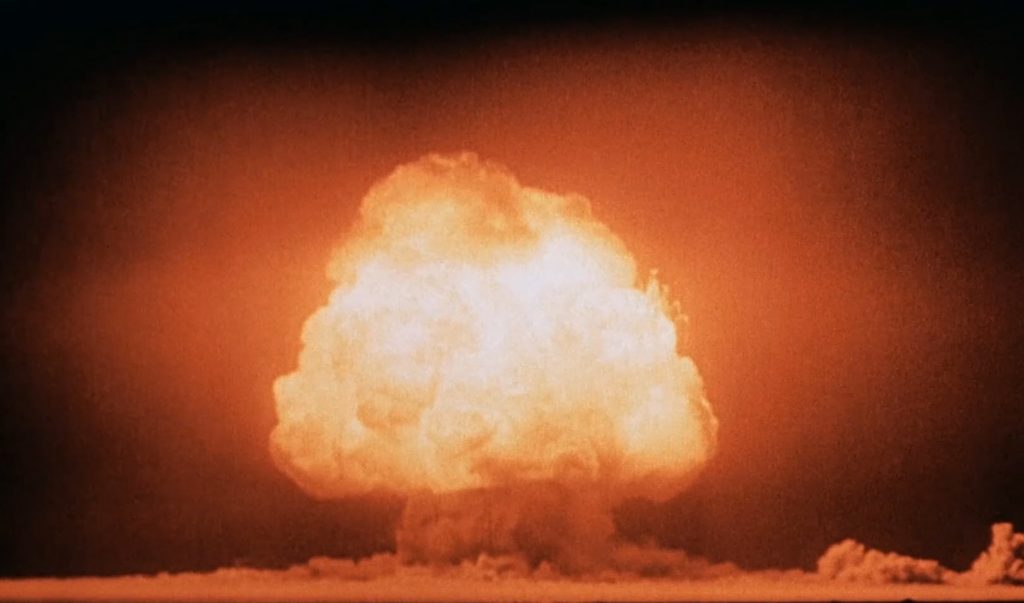

At 5:29 a.m. on July 16, 1945, the world’s first atomic bomb was detonated in the New Mexico desert. The bomb released a destructive power unlike anything previously experienced. It emitted the equivalent of 21,000 tons of TNT and created a fireball 2,000 feet in diameter. As one observer described the blast, “It was like being at the bottom of an ocean of light.” This test, named the Trinity Test, changed history. In this new atomic age, new superpowers emerged, new alliances were formed, and fear underscored decisions. At the heart of this transformation was the U.S. Army, who reacted to these changes to keep Americans safe. The success of the Trinity Test changed America’s foreign policy for the next 50 years.

Trinity blast. Department of Energy.

Tension between the United States and what would become the Soviet Union surfaced during the end of World War I which coincided with the Russian Revolution. The revolution led to the establishment of a new socialist government in Russia. Fear that socialist revolutionary thought might spread far outside the borders of Russia overtook the United States. Throughout the next two decades, an uneasy peace existed between the two countries who wished to maintain economic ties. During this time period, up to two-thirds of all U.S. agricultural and metal machinery exports were sent to Russia. However, the economic relationship did not translate to diplomatic ties. As U.S. diplomat George Kennan remarked, “Neither then nor at any later date, did I consider the Soviet Union a fit ally or associate, actual or potential, for this country.”

The relationship between the two countries remained uneasy until World War II, when they found a common enemy in Nazi Germany. However, after the war that new relationship fell apart as old distrust resurfaced and intensified. At the Potsdam Conference, in the summer of 1945, the three Allied powers of the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union met to negotiate the terms for the end of World War II. The three countries confirmed plans to demilitarize Germany, divide the country into four occupation zones, and established a Council of Foreign Ministers to draft peace treaties with Germany’s former allies. Absent from the Conference’s outcome was a plan for Eastern Europe and Germany. As a result, in countries east of Germany, coalition governments sprung up as the war ended. Those governments were influenced by Soviet liberating armies who remained in charge of transportation, relocation, and internal security. The Soviet commanders used their influence to quell all political viewpoints in opposition to communism. Unsurprisingly, coalition governments in Eastern Europe turned into permanent communist governments sparking fears that communism would soon overtake all of Europe. The relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union deteriorated further following the Soviet’s successful test of their own nuclear weapon in April 1949. In that instant, the Soviet Union officially transformed from an ally to a threat and that transition had long-lasting consequences for the U.S. Army.

During World War II, the Soviet Union built the largest army in the world. On June 22, 1941, the German army launched a surprise invasion of the Soviet Union and eventually advanced hundreds of miles to the towns surrounding Moscow, the capital. In response, the Soviet Union passed a new wartime conscription act, lowering the age of enlistment, to bolster their numbers. The strategy worked and at its peak, the Soviet Army numbered 12.5 million soldiers. Following the war, the Soviet armed forces demobilized from their wartime enlistment numbers. However, by 1950 they still outnumbered western military units in Europe by ten to one. Additionally, reports from the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) produced dire warnings. One estimate theorized that the Soviet Union was capable of expanding its army to 8 million men within 30 days’ notice. These reports alarmed American military planners who believed that the U.S. did not have sufficient troops or the resources available to respond to a provocation by the Soviet Union.

American military planners believed that provocation by the Soviet Union was a foregone conclusion. It was not a matter of if an attack would come but when. Military planners believed the most likely route of invasion would come through an area known as the Fulda Gap. This was the most direct route from Soviet occupied areas in East Germany to West Germany and led directly to France and the English Channel. Also along this route were major industrial cities that produced vital resources to supply an army. Those same resources would be advantageous to advancing Soviet attack. Based on this scenario, western armies constantly stood at the ready to deploy.

An M59 armored personnel carrier in Miltenberg, Germany during a training exercise, February 1958. Center of Military History.

Faced with the looming threat of a Soviet invasion, deterrence became an important tool used by the Army to combat perceived threats of the Cold War. To complement this policy of deterrence, the Army built new outposts in Europe and undertook new training exercises designed to combat the realities posed by the Soviet Union’s army. Throughout the 1950s, the U.S. Army built up its physical presence in Germany. On September 10, 1950, President Truman authorized a substantial increase in the strength of U.S. forces in Europe. The president’s announcement reinforced the United States’ commitment to the defense of Europe and spurred the effort to increase the American presence on the continent. At that time, the Seventh Army established its headquarters at Stuttgart, Germany with the primary mission of training and combat readiness. On January 1, 1951, the Seventh Army’s military strength measured over 44,000 Soldiers and by the end of the year, the number reached over 160,000 Soldiers. The Army’s commitment of manpower to Germany demonstrated the seriousness of the perceived threat at the time.

Soldiers arrive in Bremerhaven, Germany, 1947. Center of Military History.

An influx of Soldiers in Europe required regular and consistent training on how to respond to possible attacks from the Soviet Union. Soldiers stationed in Germany throughout the Cold War strove to maintain the combat readiness necessary to respond to an emergency within hours. Their daily routines and training prepared them for the worst-case scenario, a surprise attack. The memory of Japan’s attack at Pearl Harbor was still fresh in the minds of senior officers. Officers incorporated the prevention of surprise attacks into training manuals and exercises. Soldiers maintained a 24 hour vigil at observation points along the border between Germany and the Soviet Union. Jeeps and armored cars patrolled the length of the border daily covering the entire border at least twice a day, once in daylight and once at night. Soldiers worked 12-hour shifts operating no further away than ten kilometers from the border in a jeep with a mounted .30 caliber light machine gun. Soldiers also established permanent and temporary observation points manned by a minimum of three Soldiers: one Soldier to keep watch, one to record any notable observations and work the radio, and the third to provide security.

An Honest John rocket on display at Darmstadt, Germany in May 1956. Center of Military History.

In addition, troops routinely completed a series of practice alerts and musters to ensure that Soldiers could reach their battle positions in the shortest amount of time possible. The exercises included timed assembly of personnel and equipment, packing and loading supplies and ammunition, and moving all into simulated assembly areas. The requirement was for the entire Seventh Army to begin movement to the battlefield within two hours of an alert.

As rumors of Soviet nuclear advances infiltrated the West, the presences of Soldiers on the border did not seem adequate to combat an invasion that might involve a massed infantry attack or nuclear weapons. In 1954, the CIA had estimated that the Soviet Union possessed as many as 200 plutonium weapons that were in a state ready to be deployed. As a result, President Eisenhower implemented a new national security policy called the “New Look” in response to the Soviet threat. Eisenhower believed that the nation should focus on its atomic arsenal to retaliate against any foe that directly threatened national interests. The military posture would shrink defense budgets to ensure a strong peacetime economy. As a result, the Army placed a greater reliance on atomic weapons focusing much of its attention on developing and procuring rockets, missiles, and other artillery munitions capable of delivering atomic warheads.

In May 1950, the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama was tasked with designing a special purpose, large caliber, field artillery rocket. The result was a rocket nicknamed the “Honest John” that was successfully tested in June 1951 at the White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico. The Honest John was the Army’s first nuclear-capable surface-to-surface rocket meaning that it launched a nuclear weapon from the ground to strike a target on the ground. This weapon was different than the one developed during World War II, which were dropped from the air to a target on the ground. The Honest John had a smaller explosive power and could be deployed on a specific target without causing widespread destruction and radioactive fallout. More importantly, it could be assembled into position within five minutes. Honest John rockets were the first in a series of new nuclear weapon systems that were developed to protect Soldiers from an advancing army while simultaneously delivering a powerful blow to the enemy.

In addition to large nuclear weapons like the Honest John Rockets, the Army also developed smaller and more portable weapons to be deployed quickly when confronted with an advancing army. The Davy Crockett was the Army’s first portable nuclear weapons systems. Named after the folk hero, Soldier, and frontiersman, the weapon was meant to be hand carried and fired by a three man crew. The Army deployed the first Davy Crockett systems at the Fulda Gap in West Germany—the expected invasion route of a Soviet advancing army. It was lethal to any person within a quarter-mile radius and those within 500 feet would be exposed to enough radiation to be killed within minutes or hours, even in the protection of an armored tank. These weapons were meant to delay an advancing army, giving U.S. Soldiers time to mount a defense.

A three-man crew prepares to fire a Davy Crockett in December 1959. Center of Military History.

As these weapons were deployed in Europe, the Army ensure that their delivery was published in local newspapers. Images of the Honest John Rockets were printed in publications around Germany and were picked up by media across the border in Eastern Europe. The Honest Johns were frequently part of military parades in Germany where they were viewed and photographed by locals. The U.S. Army used these opportunities to demonstrate the United States military strength and nuclear superiority. These messages were intended to intimidate and deter Soviet aggression.

Tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War created unique challenges for the U.S. Army. It required the Army to implement new strategies, build new outposts, and develop new weapons systems to carry out the United States Cold War foreign policy until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. The establishment of the Russian Federation in the same year would establish new conditions for the Army to adapt to in the future.

Jennifer Dubina

Museum Educator

Sources

Bacevich, A.J. The Pentomic Era: The U.S. Army between Korea and Vietnam. Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press, 1986.

Carter, Donald A. Forging the Shield: The U.S. Army in Europe, 1951-1962. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 2015. https://history.army.mil/html/books/045/45-3-1/index.html

Stivers, William, and Donald A. Carter. The City Becomes the Symbol: The U.S. Army in the Occupation of Berlin, 1945-1949. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 2017. https://history.army.mil/html/books/045/45-4/index.html

Weisberger, Bernard A. Cold War, Cold Peace: The United States and Russia since 1945. New York: American Heritage, 1985.