You say we’re fighting for democracy. Then why don’t democracy include me?

– Langston Hughes

African Americans have served their country in every American conflict since the Revolutionary War. Yet despite their willingness to serve, Black Soldiers faced discrimination both within the military and at home. World War II brought an opportunity for change. The call for men to fill military ranks and workers to supply wartime factories gave civil rights leaders an opportunity to demand equality. Their demands combined with the courageous service of Black veterans led to President Harry Truman’s Executive Order 9981, which desegregated the armed forces and marked a tangible step toward ending segregation in America.

Prior to World War II, racial segregation impacted almost every aspect of American life, including the military. In 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation allowed Black Soldiers to enlist in the Army through the creation of the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Although the USCT was disbanded at the end of the Civil War, the Army established its first, permanent all-Black regiments in 1866. Buffalo Soldiers, members of the all-Black 10th Cavalry Regiment, fought on the western frontier during the Indian Wars (1866-1897). When not fighting, Soldiers built roads and telegraph lines, guarded stage coach and mail routes, and escorted supply trains. In the twentieth century, Buffalo Soldiers also fought alongside Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in Cuba during the War with Spain.

Buffalo Soldiers of the 25th Infantry, Fort Keogh, Montana, 1890. Library of Congress.

Black Soldiers continued to serve in the regular Army and the National Guard through World War I. The 369th Infantry Regiment was the first all-Black unit activated for overseas service during the war. In Europe, they were reassigned to a French unit and stationed on the frontlines. There they earned the nickname, “Harlem Hellfighters.” Throughout their 191 days in combat, none of the regiment’s men were captured and no ground they defended was lost. In France, the 369th were treated like heroes and awarded the French Criox de Guerre, the equivalent of America’s highest military honor, the Medal of Honor.

Soldiers of the 369th awarded the Croix de Guerre for gallantry in action. National Archives.

Black World War I veterans had hoped their military service would help end racism at home. Returning home, however, they were met with violence. Race riots proliferated throughout the country. Thousands of people were killed, injured, or left homeless in the summer following the armistice. In 1919, at least 75 African Americans were lynched including 11 Soldiers during what came to be known as “Red Summer.” The violence continued into the following decades and white supremacist groups such as the Ku Klux Klan grew in number and prominence.

World War II prompted a new call for Soldiers to fill the country’s military ranks. However, the experiences following the First World War were still fresh in the mind’s of African Americans. One man, James G. Thompson, captured those feelings in a letter to the editor of the Pittsburgh Courier, when he asked, “Should I sacrifice my life to live half-American?” His question struck a nerve for Black Americans. His words became a rallying cry known as the Double V Victory Campaign, which called for two victories—one over discrimination at home and another over fascism abroad. It was circulated in Black newspapers and spread through posters, baseball games, the “Doubler” hairstyle, war bond drives, and beauty pageants.

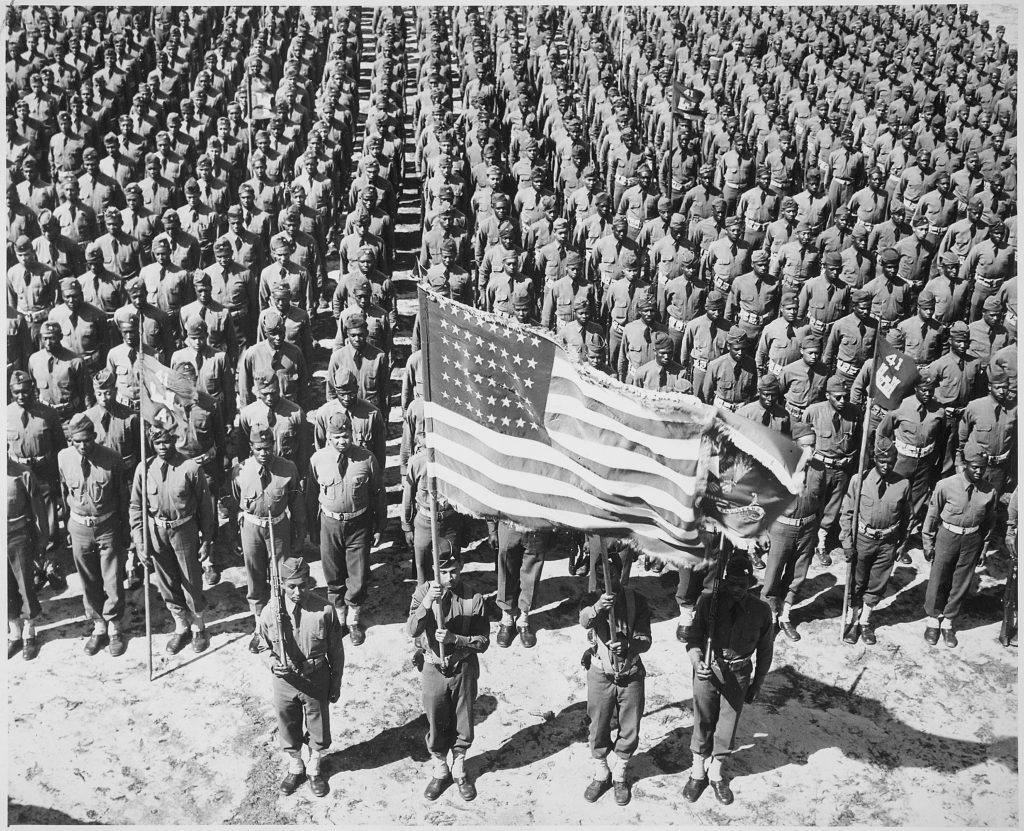

Victory over discrimination at home meant desegregating the military. Black enlistees were often disqualified based on biased intelligence exams that privileged white applicants. Often their names were added to the bottom of eligibility lists to keep numbers low. At the start of the war, there were only four all-Black regiments in the Army. A first major success came with the passage of the 1940 Selective Service Act that required draftees to be enlisted and trained regardless of race which expanded available opportunities.

On Parade, the 41st Engineers at Fort Bragg, North Carolina in color guard ceremony. National Archives.

Despite this progress, nearly 85% of Black Army enlistees were assigned to labor and support battalions. Black Soldiers often stood out for their exceptionalism in these positions. Soldiers like those assigned to the 666th Quartermaster Truck Battalion, part of the “Red Ball Express,” earned high praise from General Eisenhower who called them “the lifeline of the Army.” Working 24 hours a day, seven days a week, these Soldiers traveled through enemy territory to deliver much needed rations, weapons, and ammunition to Soldiers on the front line.

Black women also contributed to the Allies’ success. The Women’s Army Corps 6888th Central Postal Battalion were the only all-Black, all-female unit sent overseas. They kept mail flowing to nearly 7 million Soldiers in the European Theater of Operations. When they arrived in England in 1945, they encountered the monumental task of delivering millions of backlogged packages and letters in addition to continuously incoming mail. The 6888th cleared the backlog in three months. They were so successful that they were sent to France to continue the same work.

In spite of these successes, civil rights leaders and Soldiers demanded the right to fight in combat. As the war progressed and manpower reserves dwindled, Black Soldiers were given the opportunity to prove themselves on the battlefield. One unit, the 761st Tank Battalion, joined the frontlines after D-Day. The 761st spent 183 days in combat and were credited with liberating towns in Belgium, France, and Germany. They drove further into enemy territory and remained on the front longer than any other armored battalion.

Members of an artillery unit stand by and check their equipment while the convoy takes a break, November 9, 1944. Cropped. Library of Congress.

Like World War I veterans 20 years earlier, Black Soldiers returned home hoping that their wartime service would bring equality. However, returning Soldiers were greeted with racial discrimination and violence. One incident that created national outrage centered on Sgt. Isaac Woodard, a Black Soldier back from overseas. As Woodard traveled from Georgia to North Carolina, a white police officer attacked and permanently blinded him. The attack happened while Woodard was wearing his Army uniform. He was not the first or the only Black Soldier to endure this type of racial violence. Throughout the country, mobs attacked Black servicemen and six servicemen were lynched. News of the violence reached President Truman, who declared, “We’ve got to do something.”

Outraged by the violence, inspired by Black Soldiers’ valiant service overseas, and pushed by civil rights leaders at home, President Truman reconsidered America’s long held segregation policies. As a first step, Truman commissioned a Presidential Committee on Civil Rights to make recommendations to improve civil rights. The committee’s report, “To Secure These Rights,” advocated for an end to race based military policies. The report stated, “prejudice in any area is an ugly, undemocratic phenomenon, in the armed services…it is particularly repugnant.” The report was a commitment on the part of the Federal government to improve civil rights. It was the first of its kind since the ratification of the 15th amendment in 1870, which granted Black males the right to vote.

President Truman wanted to make change quickly. Fearing that congressional action would take too long and looking ahead to his upcoming reelection campaign, Truman used executive action. On July 28, 1948, he issued Executive Order 9981 which stated that “for all those who serve in our country’s defense…it is hereby declared…that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons without regard to race, color, religion or national origin.” When asked if the order meant an end to segregation, the president stated simply, “Yes.”

Members of the Women’s Army Corps at Camp Stoneman, California, April 1946. United States Army Signal Corps, Harry S. Truman Library & Museum.

Desegregation in the military did not happen overnight. The Air Force, Army, Coast Guard, Marine Corps, and Navy implemented the order on different timelines. President Truman created the President’s Committee on Equality of Treatment and Opportunity in the Armed Services, or more commonly known as the Fahy Committee, to oversee implementation and ensure each service complied with desegregation.

The last service to fully integrate was the Army who viewed segregation as a military necessity. The policy of “separate but equal,” the Army argued, did not discriminate because it gave everyone equal opportunity. The Fahy Committee investigated the Army’s personnel practices and proved that segregation resulted in discrimination and inefficiency. The committee found that while Black Soldiers could enroll in any Army school, they could only enroll if an all-Black unit had an opening in that specialty. Since there were fewer all-Black units and those units were limited in their specialties, Black Soldiers were unable to pursue their own interests. In April 1949, of the 106 Army courses open to recruits, only 21 were open to Black Soldiers. Further, the committee found that segregation weakened morale, drained resources, and created an inferior force.

The Army abandoned its support of segregation based on the committee’s investigation. Full integration was realized during the Korean War. The influx of new recruits forced the Army to adhere to the committee’s recommendations and integration took place rapidly to meet the demands of war. By the end of the war, all combat units in Korea as well as training units in the United States had been desegregated. In Europe, changes took place more slowly. In March 1951, the Army’s European Command issued a statement to the force stating, “it is the policy…to assign individuals to units which can most effectively utilize their qualifications regardless of race.” In the same year, the Army closed the Kitzingen Training Center in Germany, designated for Black Soldiers. The closure meant that African American Soldiers would be processed and trained in integrated facilities before placement into integrated units. In 1954, the Army, in collaboration with Johns Hopkins University, released a study titled “Project Clear.” Examining the effects of segregation on the Army, the study found that segregated units limited the overall effectiveness of the Army. The Supreme Court, ruling in Brown v. the Board of Education in the same year, further confirmed the end of segregation in the Army. By the end of 1954, the last all- Black Army unit was disbanded.

World War II invigorated the struggle for civil rights and equality in the United States. Civil rights leaders capitalized on new opportunities in the military and at home to demand equity. Their efforts culminated in Executive Order 9981 which marked a first Federal attempt to limit segregation at home. Yet, while World War II ushered in positive changes for African Americans, they continued to live in segregated settings and endure discrimination and disenfranchisement outside of the military. Segregation had been eradicated in the military but there was still much work left to do both in the ranks and at home.

Jennifer Dubina

Museum Educator

Sources

Edgerton, Robert B. Hidden Heroism: Black Soldiers in America’s Wars. Colorado: Westview Press, 2001.

Dalfiume, Richard M. “The Fahy Committee and the Desegregation of the Armed Forces” The Historian 31, no. 1 (November 1968): 1-20.

Department of the Army Historical Division. Integration of Negro and White Troops in the U.S. Army, Europe, 1952-54(U). 1956 . https://history.army.mil/html/documents/coldwar/integr_usareur/index.html#toc.

Kersten, Andrew. “African Americans in World War II.” OAH Magazine of History 16, no. 3 (Spring 2002): 13-17.

Leiker, James N. “Freedom, Equality, and Justice for All? The U.S. Army and the Reassessment of Race Relations in World War II.” Army History no. 82 (Winter 2012): 30-41.

McGregor, Morris J. Jr. Integration of the Armed Forces, 1940-1965. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 2001.

McGuire, Philip. “Desegregation of the Armed Forces: Black Leadership, Protest and World War II.” The Journal of Negro History 68, no. 2 (Spring 1983): 147-158.

Rolland-Diamond, Caroline. “’A Double Victory?’ Revisiting the Black Struggle for Equality during World War Two.” Revue francaise d’etudes americaines 137, (January 2013): 94-107.

Schamaun, Annie. “Executive Order 9981 and the Racial Desegregation of the American Armed Services.” Spring 2010.

Wright, Karin. Soldiers of Freedom: An Illustrated History of African Americans in the Armed Forces. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 2002.

Additional Resources

“African Americans in the U.S. Army.” Center of Military History. Last modified January 31, 2021. https://history.army.mil/html/topics/afam/index.html.

“African Americans in the U.S. Army.” United States Army. Accessed 21 June 2021. https://www.army.mil/africanamericans/.

“Experiencing the War: Stories from the Veterans History Project.” Library of Congress. 7 May 2018. https://www.loc.gov/vets/stories/ex-war-desegregation.html

“Pictures of African Americans during World War II.” National Archives and Records Administration. Last modified June 17, 2021. https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/ww2-pictures.