Ely S. Parker

Brevet Brigadier General

7th Division

1828 – August 31, 1895

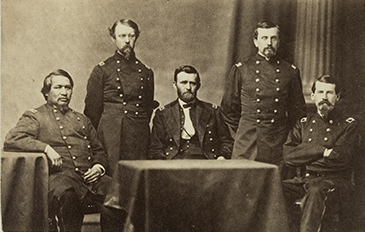

Left to right: Brig. Gen. Ely S. Parker, Col. Adam Badeau, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, Lt. Col. Orville E. Babcock, and Lt. Col. Horace Porter, circa 1865. John A. Whipple; Harvard Art Museum

It can be hard trying to balance between two worlds. Ely S. Parker spent his life navigating between the world of his Seneca Nation family and the Civil War era in which he lived. His numerous attempts to integrate into mainstream society were repeatedly rebuffed due to his ethnicity and the color of his skin. However, his determination to succeed, combined with some open-minded individuals he met throughout his life, led to Parker making a name for himself in Army and American history.

Ely Samuel Parker was born in 1828 on the Tonawanda Reservation near Buffalo, New York into the Wolf Clan of the Seneca Nation. The Seneca were part of the League of the Haudenosaunee, also known as the Six Nations of the Iroquois or Iroquois Confederacy. At birth, he was named Hasanoanda, which translates to “Leading Man.” While raising their children in the traditions and language of the Seneca Nation and the Haudenosaunee, his parents were also pragmatic. They sent their children to a nearby Baptist mission school to learn English and receive an American education. It was at that school that he began to go by the name Ely (pronounced like “freely”).

Parker thrived in school. By the time he was in his teens, his fluency in English made him instrumental to Tribal leaders. He began to accompany them on their trips to Albany, New York and Washington, D.C. in defense of tribal treaties with the United States government. His observations of the interactions between the Haudenosaunee and the United States led Parker to want to become a lawyer to better help his people and protect their lands. Despite his extensive study of the law, and even working in a New York law firm for three years, Parker was prohibited from taking the New York State Bar exam. At the time, most Native Americans were not considered United States citizens, and New York State required all test-takers to be citizens. Parker’s repeated attempts to take the test were denied.

During this time, he met Lewis Henry Morgan, a lawyer and anthropologist interested in Native American culture. The two men formed a life-long friendship. Parker gave Morgan access to the world of tribal knowledge and traditions. In turn, Morgan introduced Parker to white society. While Parker considered acceptance into white society important, he remained dedicated to fighting on behalf of the Seneca and Haudenosaunee people. His influence led to his election as sachem, or chief, of the Tonawanda in 1851. Upon his selection, Parker took the name Donehogawa, or “Open Door.” He held this position for the rest of his life.

Parker eventually realized that a career in law would never come to fruition. Instead, with Morgan’s help, he turned to civil engineering, a field where his advancement would not be limited due to his race. He attended the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. Upon completing his studies, he worked on the expansion of the Erie Canal in Rochester, New York before moving to Galena, Illinois in 1857 where he supervised the construction of a federal customshouse. There, he met a United States Military Academy at West Point graduate-turned-store clerk by the name of Ulysses S. Grant. Like Morgan, Grant became a lifelong friend who had a great impact on Parker’s life and career.

At the onset of the Civil War, Parker tried to join the Army and recruit other Haudenosaunee men to enlist. His efforts were met with constant refusal. New York Governor Edwin D. Morgan and Secretary of War Simon Cameron turned the men away. Secretary of State William Seward also refused their admittance, stating that the war was “an affair between white men.” Grant interceded in 1863 and Parker finally received his commission.

Following his admittance into the Army, Parker became chief engineer of the 7th Division and served during the siege of Vicksburg and the Chattanooga Campaign. Following Chattanooga, Parker was appointed Grant’s aide-de-camp and served as his secretary writing most of Grant’s letters. He was also promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. Parker served in this capacity through the end of the war.

Perhaps Parker’s most well-known military moment was drafting the terms of surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. When he was done reviewing the document, General Robert E. Lee extended his hand to Parker and stated, “I am glad to see one real American here.” Parker shook the defeated general’s hand and responded, “We are all American.” That same day he was promoted to brevet brigadier general, the highest military rank awarded to any Native Soldier in the war. To be brevetted meant that while Parker was rewarded for his admirable conduct throughout the war, he did not receive the corresponding authority or pay.

After the war, Parker continued to walk the line between his two worlds, not just where his career was concerned. In 1867 he sent shockwaves throughout Washington society and the League of the Haudenosaunee when he married a white woman named Minnie Sackett. Their marriage took place a full one hundred years before the Supreme Court legalized interracial marriage at the federal level in Loving v. Virginia.

Following Grant’s successful presidential election in 1868, he nominated Parker as the commissioner of Indian Affairs, the first Native American to hold the job. The two men worked together on President Grant’s Peace Policy between the U.S. government and Native tribes. The policy was supposed to protect Native American interests and land by reverting their care into the hands of the War Department instead of civilian agencies, which were viewed as corrupt. Despite Parker and Grant’s good intentions, in reality, the policy led to further forced assimilation with little to no regard for Native people’s tribal lands, traditions, or languages.

Parker was initially seen as an excellent choice for commissioner, however, politics and racism eventually came into play and opponents accused him of misconduct and fraud. While an 1871 Congressional committee cleared him of all charges, he was stripped of all the powers allotted to his office. Parker resigned in August 1871. He never held political office again.

Parker and his wife moved to Fairfield, Connecticut, and he eventually found a job as a businessman and amassed quite a fortune on Wall Street. His luck, however, did not last. The economic Panic of 1873 hit his fortune hard and he lost all his money. Parker was once again forced to shift careers. He became a desk clerk with the New York City Police Department while also dabbling in public speaking. By the end of his life, Parker battled kidney disease and diabetes and suffered a series of strokes. He died on Aug. 31, 1895. He was buried with full military honors.

Ely S. Parker spent his life trying to navigate being a Native American man in a white man’s world. Despite the blatant prejudice he was subjected to, his groundbreaking achievements throughout his life led the Bureau of Indian Affairs to name its headquarters in Virginia in his honor.

Jordan Ginder, Graduate Historic Research Intern

Caitlin Healey, Education Specialist

Sources

Adams, James Ring. “The Many Careers of Ely Parker.” National Museum of the American Indian, Fall 2011. https://www.americanindianmagazine.org/sites/default/files/2018-02/Fall2011.pdf.

Contrera, Jessica. “The Interracial Love Story That Stunned Washington – Twice! – in 1867.” Washington Post, February 13, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/02/13/interracial-love-story-that-stunned-washington-twice/.

DeJong, David H. “Ely S. Parker: Commissioner of Indian Affairs (April 26, 1869–July 24, 1871).” In Paternalism to Partnership: The Administration of Indian Affairs, 1786–2021, 139–45. University of Nebraska Press, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv2cw0sp9.29.

“Ely Parker Biography.” PBS, April 4, 2000. http://www.pbs.org/warrior/content/bio/ely.html.

“Ely S. Parker Building Officially Opens.” U.S. Department of the Interior, December 21, 2000. https://www.bia.gov/as-ia/opa/online-press-release/ely-s-parker-building-officially-opens.

“Ely S. Parker.” Historical Society of the New York Courts. Accessed August 8, 2022. https://history.nycourts.gov/figure/ely-parker/.

Stockwell, Mary, and Zócalo Public Square. “Ulysses Grant’s Failed Attempt to Grant Native Americans Citizenship.” Smithsonian Magazine, January 9, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/ulysses-grants-failed-attempt-to-grant-native-americans-citizenship-180971198/.

Vergun, David. “Engineer Became Highest Ranking Native American in Union Army.” U.S. Department of Defense, November 2, 2021. https://www.defense.gov/News/Feature-Stories/Story/Article/2781759/engineer-became-highest-ranking-native-american-in-union-army/.

Watson, Daryl. “Biography of Ely S. Parker.” Galena and U.S. Grant Museum. Accessed August 11, 2022. https://www.galenahistory.org/research/bio-sketches-of-famous-galenians/biography-of-ely-s-parker/.

Additional Resources

Hansen, Terri. “How the Iroquois Great Law of Peace Shaped U.S. Democracy .” PBS, December 17, 2018. https://www.pbs.org/native-america/blogs/native-voices/how-the-iroquois-great-law-of-peace-shaped-us-democracy/.

National Museum of the American Indian, Education Office. “Haudenosaunee Guide for Educators,” 2009. https://americanindian.si.edu/sites/1/files/pdf/education/HaudenosauneeGuide.pdf.

One Real American: The True Story of Ely Parker. Ulysses S. Grant Cottage Historic Site, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sP7_M1pHWbc&t=1s.

Ulysses S Grant National Historic Site. “President Ulysses S. Grant and Federal Indian Policy.” National Park Service, July 11, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/president-ulysses-s-grant-and-federal-indian-policy.htm.