European Traditions and Professional Armies

The modern armies of the world find their foundations in antiquity with the Greeks and Romans. They developed organized military structures and systems of discipline that are still used to this day. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the European continent developed into a series of nation-states controlled by hereditary royal families. These royals of the Middle Ages occupied the top tier of the feudal order and could levy taxes, as well as raise armies to fight for their interests. The 16th century brought new tactical and technological advances with the widespread use of artillery, but also saw the advent of standing armies. Near constant conflict between states and peoples, coupled with technological advancement led to a military revolution in Europe which eventually was adopted in the New World.

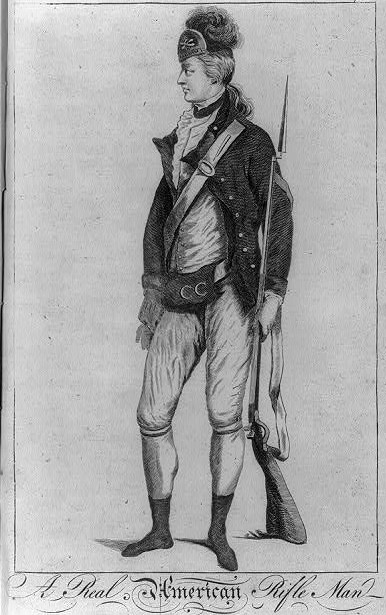

“A Real American Rifle Man,” circa 1780. Library of Congress

The military systems in place during the 18th century greatly contributed to the military origins of the United States. During this period, Europe conducted a limited style of war. Skirmishes between soldiers of the different lands occurred regularly in the colonies with contentions over borders and resources. The militia system, which was based on medieval precedent, was transplanted from England to the colonies as a way to train and prepare colonists to react to emergencies. Many of the colonies adopted a compulsory militia model where men were required to appear for a certain number of training days a year. These militiamen were usually required to purchase their own weapons, ammunition, clothing, and food for the duration of their service. Militias tended not to be well-organized or disciplined, with most men trying to serve quickly and return home, but made up for their failings with heightened enthusiasm under threat.

The British Army, on the other hand, was truly a professional organization. It was organized under a class structure where men from the aristocracy or upper classes of society served as officers, whereas men of the lower classes composed most of the enlisted ranks. The British soldier was a professional who trained for two years under a system of strict military discipline. The armies of the period were primarily composed of infantry, artillery, and cavalry. The infantry deployed linear tactics with men marching in column and deploying into lines three or four ranks deep. These men stood shoulder to shoulder to deliver the greatest mass of firepower in a given area, usually with murderous results. This rigid structure and discipline led many military experts of the period to believe that no body of poorly trained civilians could ever stand before a professional army.

Colonial Rule, Revolution, and the Formation of the Continental Army

The colonies had, for over a century and a half, developed their own identity separate from Great Britain. The harsh American climate and terrain had fostered a spirit of individualism and self-reliance, almost absent of English tradition. Great Britain could sense this growing divide between themselves and the colonies. In 1763, 10,000 British regulars deployed to increase their presence in the colonies and to prevent conflict between colonists and Native Americans. This act planted the seeds of revolution within the colonists, for they were forced to bear the cost of this force of British regulars in the form of taxes. Britain passed the Sugar Act, the Stamp Act, and the Townshend Acts, which resulted in steep price increases for regular commodities such as sugar, molasses, tea, paper, and building materials. The colonists viewed these acts as an infringement on their civil liberties, so groups such as the Sons of Liberty formed to fight back against British control.

“The Destruction of Tea at Boston Harbor” by Currier & Ives, 1846. Library of Congress

On the night of December 16, 1773, the Sons of Liberty boarded ships at Griffin’s Wharf in Boston, Massachusetts, and dumped 342 chests of British East India Company tea into the Boston Harbor. These colonists were angry with Great Britain for imposing these taxes without colonial representation in the British Parliament, so they acted in defiance of these acts; no tea meant no taxes. Britain responded severely to the Boston Tea Party, they passed a series of acts meant to punish the colonists for their defiance by suppressing their civil liberties even further. These came to be known as the Intolerable Acts, which required the colonists to pay for the destroyed tea, quarter British troops in their homes, and ended free elections in Massachusetts. Britain believed that these acts would put an end to the spirit of colonial rebellion, but they only served to further enrage them.

Tensions between Britain and the colonies continued to escalate over the issue of taxation, leading to more violent encounters between the two entities. On April 19, 1775, this increasing violence exploded into a revolution when British troops fired on colonial militiamen at Lexington, Massachusetts. The Battles of Lexington and Concord began as a civil disturbance but transformed the conflict into open warfare. Two months later on June 14, 1775, the Continental Congress voted to create the Continental Army as a united colonial response against the British enemy. This new Continental Army included 10 companies of riflemen. The first men to enlist came from Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. The next day, Congress voted to appoint General George Washington as the Commander in Chief of the Continental Army.

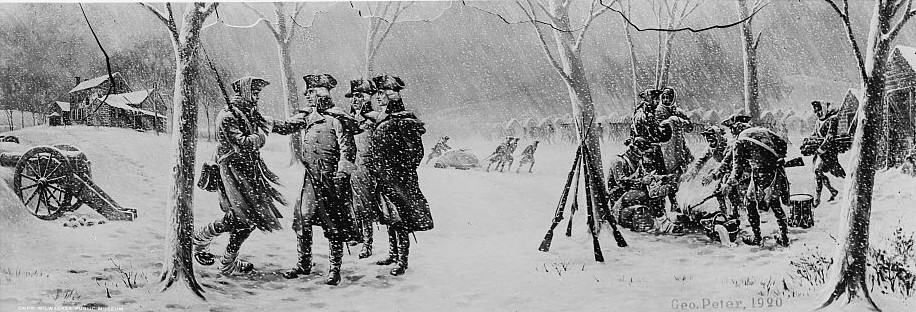

General George Washington and his Soldiers at winter camp in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania by George Peter, 1920. Library of Congress

The Cost of Independence

The Continental Army faced several challenges throughout the Revolutionary War in addition to a determined and professional enemy. They suffered from a continual lack of supplies, ammunition, arms, limited pay, and often an inconsistent supply of food. The colonies spanned great distances, so official communications and supplies were constantly delayed, and marching was a long and difficult undertaking. Time of service for these enlisted men became an issue as well. To solve this problem, Congress implemented the first draft in winter 1777-78 but often meant that many regiments prior were constantly understrength. Immediate leadership for these men was oftentimes inconsistent and they received no unified system of training, leading to disaster on the battlefield during the earlier part of the war. Despite all of this, Washington stood resolute in his leadership, which was ultimately a major factor in Continental success.

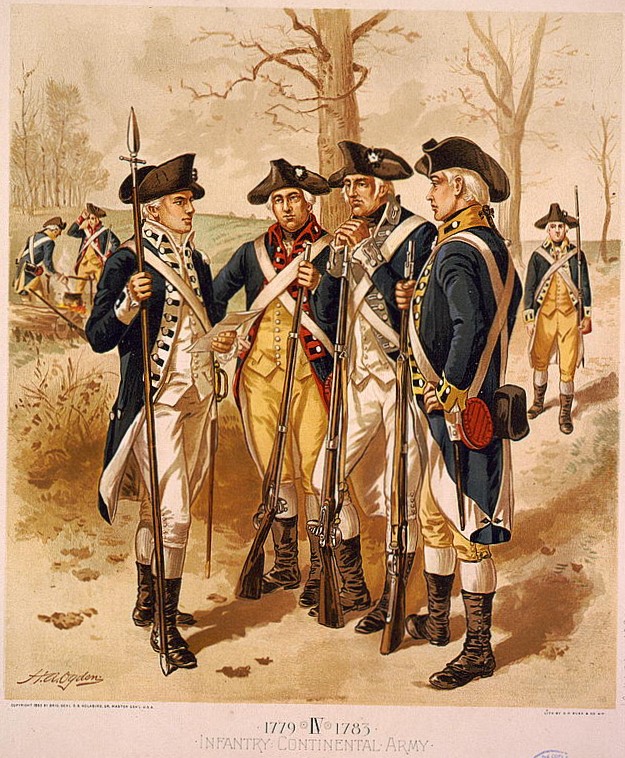

What the Continentals lacked in terms of materiel and manpower, some made up for in resourcefulness. Due to the North American environment, the colonists had developed tactics separate from their British counterparts. The British primarily fought in traditional linear formation, but some colonial units deployed guerilla-style unit tactics modeled off of their Native American neighbors. These units were commanded by one leader and were able to make on-the-spot decisions while in combat. They used the surrounding terrain to fight from areas of cover and concealment in order to leave an engagement victorious. Though these tactics were not in widespread use by the Continental Army during the war, they were employed on occasion to disrupt the British supply. The Continental Army primarily fought in linear formation, like the British, but it was the resourcefulness of their leadership that ultimately allowed the Continental Army to win the war.

“Infantry Continental Army, 1779-1783” by Henry Alexander Ogden, circa 1897. Library of Congress

From 1775 until the Revolutionary War’s end in 1783, over 231,000 men served in the Continental Army. Of that number, no more than 48,000 men served at one time, and no more than 13,000 were deployed in one place. In addition to the number of men who served in the Continental Army, upwards of 145,000 men served in colonial militias that fought alongside the Army. The Continentals endured many hardships throughout the war such as on the march to Quebec, Canada, harsh winter encampments at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, and Morristown, New Jersey, and on the Southern Campaigns. It is estimated that 6,800 Americans were killed in action, 6,100 were wounded, and upwards of 20,000 were taken prisoner. It is also believed that an additional 17,000 deaths were caused by disease and 8,000 to 12,000 died while prisoners of war.

Legacy of the United States Army

The Continental Army engaged a better organized, determined, and professional British enemy, but American tactics, self-reliance, and courage ultimately secured colonial independence. George Washington drew from the war a belief that there stands an inherent need to maintain a well-regulated militia that is trained and organized under a uniform national system. This belief is the basis on which the United States Army is organized today. The Revolution also helped to create a uniquely American ideology of a people fighting for a cause, an ideology seen time and time again on battlefields at home and abroad. The United States Army of today is rich in military tradition and honors those who fell in the name of the American ideal of freedom. Happy Birthday, Army.

Matthew Bartley

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Sources

“American Revolution Facts.” The American Battlefield Trust. Accessed April 14, 2022. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/american-revolution-faqs.

History.com Editors. “Battles of Lexington and Concord.” A&E Television Networks. History.com, December 2, 2009. https://www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/battles-of-lexington-and-concord.

U.S. Army Center of Military History. American Military History, Volume 1: The United States Army and the Forging of a Nation, 1775-1917. Washington, DC: CMH Pub, 2005.