The story of the first women graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point begins not along the banks of the Hudson River, where the school is located, but in Washington, D.C. There, on Oct. 7, 1975, President Gerald R. Ford signed Public Law 94-106, opening enrollment at the three public military academies to all eligible applicants, regardless of sex. Ford’s signature marked the end of a 30 year process to formally allow women the same opportunities as men, and marked the beginning of a long journey for a select group of women headed to their new rockbound highland home.

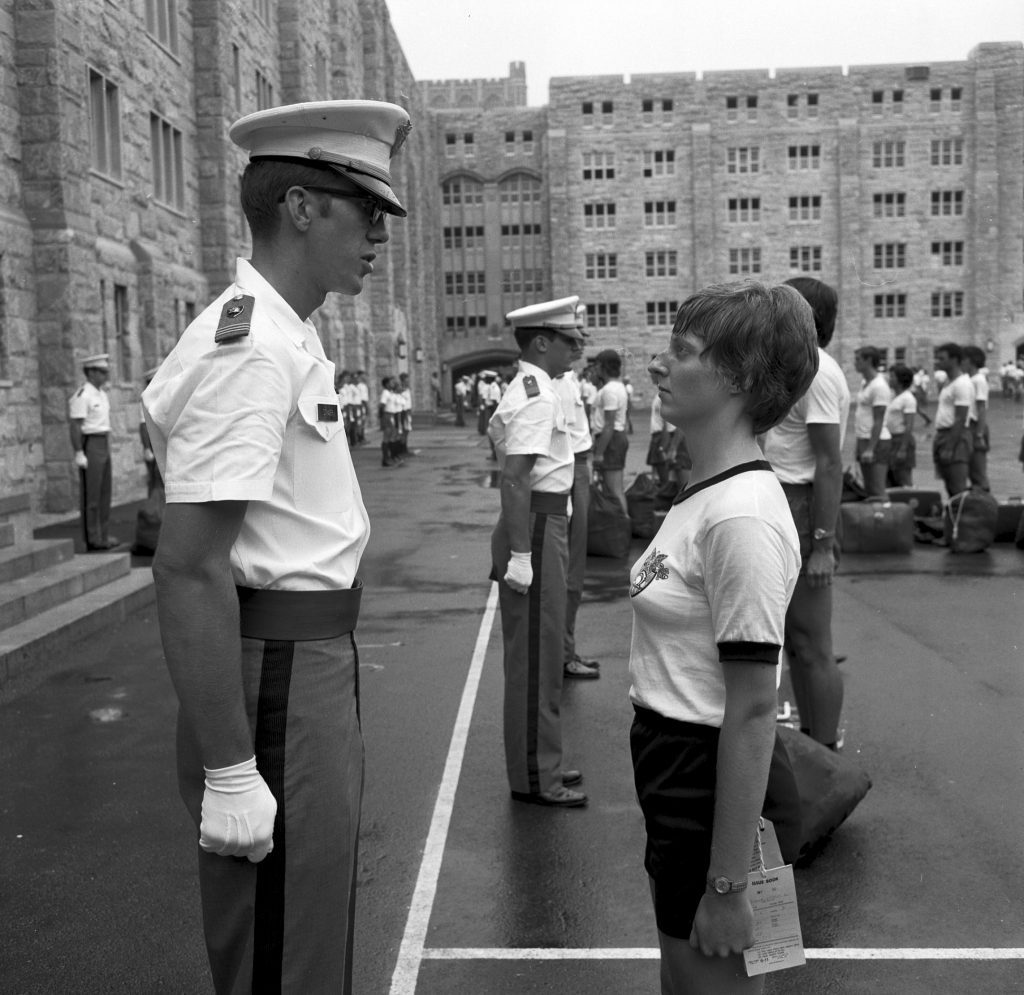

Women arrive at West Point, July 7, 1976. Department of Defense

Arrival

Exactly 10 months later, on July 7, 1976, the first 119 women arrived at West Point for “Reception Day” and the start of their Cadet Basic Training. The decision to enroll varied, but a call to serve resonated within each one. Nancy Gucwa, from Staten Island, New York, recalled seeing the motto “Duty, Honor, Country” on a brochure at her home. “Just the opportunity to be built into a leader, have character and to serve my country was very appealing,” said Gucwa. Lillian Pfluke, a native of Palo Alto, California, recalled that the challenges at West Point, such as “shooting guns and jumping out of airplanes sounded a lot more fun than just studying engineering at a civilian college.” Pfluke’s sense of adventure and Gucwa’s call to duty pervaded the entire class of women, and for good reason. They represented the very best of their respective home towns across the country and were the few women remaining after a vigorous selection process that whittled the number of applicants from about 600 women to the final 119 who entered the gates on that July day. Their presence at the military academy followed a rowdy public debate within West Point and the nation they sought to serve. On one side were men like Gen. William Westmoreland, the recently retired Army chief of staff and commander of all U.S. forces in Vietnam. To him, any woman who could succeed at West Point was “a freak, and we’re not running the military academy for freaks.” On the other side were numerous politicians, military leaders, and West Point graduates who repudiated people like Westmoreland and believed in the capacity of women to succeed at the academy. To them, the inclusion of women merely brought West Point up to the standards that the Reserve Officer Training Corps and Officer Candidate School commissioning programs upheld for almost a decade prior to the admission of women into the service academies and provided the post-Vietnam Army more qualified recruits.

Upon arrival, the women of West Point met a similar range of opinions in the minds of their peers. Lt. Col. Carol Barkalow, a member of the first graduating class of women, remembered that while the majority of male cadets simply abided by the new dynamics, a “vocal minority sometimes made it hell.” Pat Locke, a prior service Army veteran from Detroit, recalled that as one of only two African American women at the academy, she experienced an even greater feeling of isolation and resentment from her predominantly white male peers. Pfluke noted that even the seemingly minor torments, when suffered daily for years, took a toll on the academy women. “The constant barrage of insults, harassment, and inequities made even the strongest among us harbor self-doubts,” she said.

Those men could not fathom the idea of women’s equality in the military and increased their harassment beyond the typical abuse that freshmen endured at the time. Brenda “Sue” Fulton, another woman in the same initial class, described the hazing as a form of social stratification within West Point. Fulton remembered that the male cadets “couldn’t conceive of [women] as cadets”, but instead thought of them as “a completely different species.” Kathy Gerstein, of Clearwater, Florida, adapted to the hazing by reminding herself that “my being at West Point was not my problem, but theirs. I was not there to diminish the experience. I was there to challenge myself.” Despite some men’s attempts to “make life hell,” recalled Fulton, most of the women persevered through the torment, only to face some unintentional institutional hurdles in their way.

A platoon of cadets poses in front of Washington Hall during the first year women were allowed at West Point. Center of Military History

Since President Ford’s declaration went into effect immediately, West Point had little time to establish a foundation of equal opportunity within the academy. Women in the first class remarked that the new cadet uniform, tailored to women, used plastic zippers instead of the metal ones found on the men’s pants. As a result, dozens ripped, tore, or failed within the first day of their “plebe” year, requiring them to borrow from sympathetic male peers. Other women remembered that their shared bathrooms still had urinals in them, since the academy ran out of time to refit them before the women arrived in July. Over the next three years, the academy slowly adapted the uniforms and facilities to better accommodate women, but other institutional obstacles remained in place. Organizationally, West Point decided to cluster the 119 women into 8 to 10 person groups and allocate them only to certain companies at the academy. The thought was that these women could provide support to each other when in close proximity, but resulted in entire companies devoid of women, stoking mistrust and falsehoods in the companies without women.

Parity and Progress

Despite the obstacles that the 119 women faced upon their arrival, the majority of the women soon thrived at West Point. At the beginning of their second academic year, 69% of the first women who arrived remained at the academy, a rate only 10% lower than their male peers, and a remarkable feat given the challenges they faced. Women soon made strides in the realm of academics and athletics. In the second year at West Point, the top academic student in the class of 1980 was a woman. The nascent women’s basketball and volleyball teams won their respective state titles in their first year, earning a varsity status and their peer’s respect. Their success came about due to the tenacity of the women at the academy. Following up on a study conducted by West Point, the official academy spokesman, Maj. Miguel Monteverde, wrote that “the women, we found, are more willing than the men to push themselves past stress barriers.” Faced with greater obstacles than their peers, the first class women simply jumped over them and kept going. Their success laid a groundwork for the years that followed.

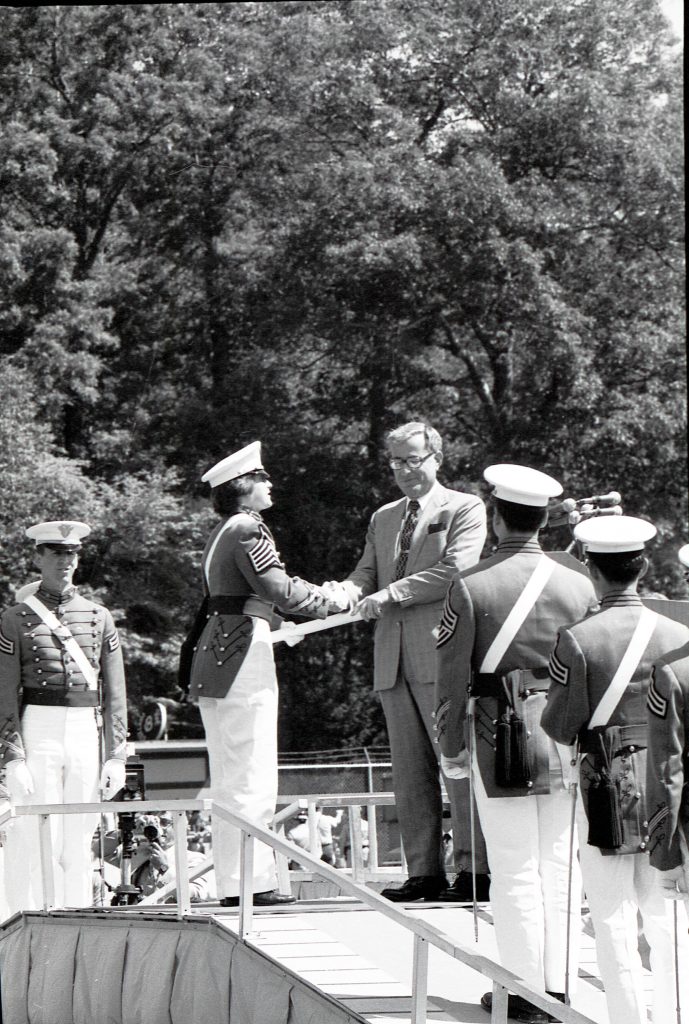

The next year, 1977, a second class of 104 women arrived at West Point. This time, West Point integrated them into every cadet company, with the first class of women reorganized to provide them supervision. The result was a dramatic drop in resignations. The second class of women lost only 14% of their total, compared to 31% of the first class, a figure only 3% higher than their male peers. By 1980, when the first class of women graduated from West Point, they held roughly 30% of all leadership positions at the academy, and one, Andrea Hollen, was the only Rhodes Scholar from the entire class. When graduation arrived on May 27, 1980, 61 of the original 119 women walked across the stage on The Plain of West Point to receive their diplomas and Army commissions.

Andrea Hollen receives her diploma, 1980. Department of Defense

More than Themselves

For many women of the first class, their accomplishments meant more than what they achieved for themselves. Secretary of Defense Harold Brown said as much as he addressed the graduates on stage. “You should be proud of the history you have made these past four years,” he said before continuing, “I take special pride in addressing this graduating class.” The women themselves echoed his remarks. Gucwa described her time at West Point as “both challenging and rewarding”, and that “the Army has greatly benefited from the contributions of West Point women graduates, and I’m proud I played a part in making that happen.”

Indeed the Army did gain greatly from the first women at the academy. Besides Hollen, who served with honor after graduating from Oxford University on her Rhodes scholarship, several women continued to contribute to the United States within and outside the military. Barkalow served for 22 years, retiring as a lieutenant colonel in the Quartermaster Corps before founding a nonprofit dedicated to housing veterans. Gucwa served until 2008, retiring as a lieutenant colonel before becoming a nun. Locke, served as a major before transitioning into the civilian world in 1995. Their success at West Point, in the Army, and within American society paved the way for future generations of women at West Point.

Women graduate for the first time in 1980. National Archives and Records Administration

Since that inaugural class of 1980, West Point women have served as the surgeon general of the Army, dean of academics at West Point, and the commandant of cadets at West Point. Younger generations of women who graduated from West Point continue to shape the Army today. For the first time ever, they lead combat arms Soldiers, earn the Ranger and Sapper tabs, and ensure the defense of our nation through their continuous honorable service.

Maj. Jane McKeon, graduate of 1980 and a former professor at West Point, recalled perhaps the most poignant aspect of her service at a 20 year reunion in 2000. There, she said several men in her class apologized for their actions and “the fact that they now understand prejudice will have a positive impact on the way they raise their sons and daughters.” For the pioneering women of that first class, no greater example of their dedication to duty can be found than that of their continuous impact on the United States and its Army.

Jacob M. Henry

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Sources

Roth, Tanya L. Her Cold War Women in the U.S. Military, 1945-1980. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021.

“How Women are Faring at West Point and Annapolis.” New York Times, September 11, 1977.

McAleer, Donna. Porcelain on Steel. Jacksonville, Florida: Fortis Publishing, 2010.

O’Connor, Brandon. “Forty Years have Passed since the First Women Graduated from West Point in the Class of 1980.” U.S. Army. May 27, 2020. https://www.army.mil/article/235994/forty_years_have_passed_since_the_first_women_graduated_from_west_point_in_the_class_of_1980.

Schloesser, Kelly. “The First Women of West Point.” U.S. Army. October 27, 2020. https://www.army.mil/article/47238/169541.

Skaine, Rosemarie. Women at War : Gender Issues of Americans in Combat. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland and Company, 1999.

“Women at West Point ‘Silly’ to Westmoreland.” New York Times, May 31, 1976.

“Women Cadets Win West Point’s Praise.” New York Times, December 8, 1977.

Further Reading

Barkalow, Carol and Andrea Raab. In the Men’s House : an Inside Account of Life in the Army by One of West Point’s First Female Graduates. New York: Poseidon Press, 1990.