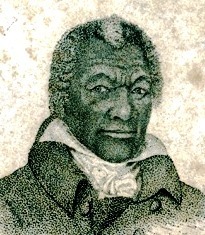

James Armistead Lafayette

Spy

Continental Army

1748 – 1830*

Engraved portrait of James Armistead Lafayette by John B. Martin, circa 1824. Library of Virginia

It is the pinnacle of irony that the United States was born from a war for independence that depended, in part, on people who were enslaved. Historians estimate that between 5,000 to 8,000 free and enslaved Black men fought on the side of the colonists during the Revolution. The Continental Army had approximately 230,000 militiamen and Soldiers, meaning that Black Soldiers made up 3.5% of patriot troops. Most of these brave men’s names have been lost to history, but a few have been remembered for their exemplary actions toward a cause and a country that did not consider them fully human. One such man was James Armistead Lafayette, who put himself at constant risk to act as a double agent to spy on the British.

The American Revolution began on April 19, 1775, and the Continental Army was officially formed less than two months later on June 14, 1775. George Washington was immediately and unanimously confirmed as the Army’s commander-in-chief. Washington, like many important and influential men of the time, was a slave-holder and was therefore uncomfortable with the idea of armed free and enslaved Black men in the Army. Those who were already part of the Army were allowed to remain, but new rules were quickly enacted on July 10, 1775, that barred additional Black men from joining the armed forces.

Those rules, however, failed to last as the war dragged on and the Army became desperate for additional troops. By 1778, Washington had become more amenable to the idea. In addition to needing the manpower, he was surrounded by enthusiastic young officers who pushed him to allow Black Patriots to fight. One such man was the Marquis de Lafayette, who would have a profound impact on James Armistead’s Army career and post-war life.

As was typical of slave records from the period, there is little documented evidence concerning James’ early life. Some sources indicate that he was born around 1748, while others list 1760 as the correct approximation for his birth. What is certain is that he was born into slavery and his life before the war was spent on a plantation owned by William Armistead in New Kent County, Virginia. James would have to seek his permission to enlist in the Continental Army, specifically the Marquis de Lafayette’s unit, in 1781.

When James enlisted it was with the understanding that he was not a free man. Once the war was over he was to return to William Armistead’s ownership. Because of this, the Marquis de Lafayette decided to use James’ status as a slave to the Continental Army’s advantage. He instructed James to spy under the guise of a runaway.

The Marquis was confident that James would be accepted into the British camp for two reasons. Firstly, as a native Virginian, his expertise on the local terrain would be a welcome addition to British intelligence. Secondly, in November 1775, the British governor of Virginia, Lord John Murray, fourth Earl of Dunmore, issued a proclamation that declared martial law and emancipated any slave who fought for the British. Lord Dunmore hoped for a full-scale slave revolt, something that many southern Founding Fathers like Washington and Thomas Jefferson were terrified of. Such a revolt never materialized. It has been estimated that only 800 to 1,000 Virginia slaves joined Loyalist forces. However, upon hearing news of the Dunmore Proclamation, as many as 100,000 enslaved people from all 13 colonies ran to British lines to escape slavery.

James successfully infiltrated Lt. Gen. Charles, Lord Cornwallis’s Virginia headquarters posing as a runaway slave who was willing to spy on American troops. As a double agent, he was tasked with gathering important details about British plans while also planting false information about the Continental Army. His race and status as a slave helped him filter between camps and listen in on conversations without raising suspicion. While acting as a British agent, he was assigned to work with the infamous American turncoat Brig. Gen. Benedict Arnold, and was told to spy on the Marquis de Lafayette by Cornwallis himself.

Perhaps the most significant contribution James made to the war effort was when he provided evidence that Cornwallis was sending 10,000 troops from Portsmouth, Virginia to Yorktown, Virginia. Thanks to his warning, Lafayette was able to alert Washington in time. Washington and French General Rochambeau incorporated James’ information into their plan for a joint American and French blockade and bombardment that caught the British off guard and eventually led to their surrender on October 19, 1781.

After the war, James returned to his enslavement under William Armistead. In 1783 the Virginia State Assembly passed an act that granted slaves who fought as Soldiers their freedom. James, however, was not among those freed. Since he was a spy and not a Soldier, his enslaved status remained unchanged. The Marquis de Lafayette intervened personally in 1784 and wrote a letter to the General Assembly detailing James’ service to the Continental Army. Even then, he did not receive his manumission until 1787. As a token of his thanks, James adopted Lafayette as his surname.

Once freed, he bought a farm not far from where he had spent his childhood enslaved in New Kent County. He married and raised a family. However, despite repeatedly petitioning for it, James did not receive an annual pension for his service until 1819, 27 years after the American Revolution ended. James and the Marquis were reunited in 1824 when the Frenchman came back to tour America. The nobleman saw James in the crowd in Yorktown and called out to him. The two men embraced in a public and fitting acknowledgment of James’s dedication and bravery during the war.

Like his birth, the year of James Armistead Lafayette’s death is speculated between 1830 and 1832. Either way, he died a free man. There is much debate over why enslaved people risked their lives for a country that did not include them among the famous lines of “all men are created equal.” While we may never know James’s reasons for serving, his courage aided in America achieving the much-needed victory that led to independence.

Caitlin Healey

Education Specialist

Sources

“An Act Freeing Enslaved Peoples Who Served as Soldiers, 1783.” Document Bank of Virginia. Accessed December 9, 2021, https://edu.lva.virginia.gov/dbva/items/show/138.

Collins, Elizabeth M. “Black Soldiers in the Revolutionary War.” U.S. Army. March 4, 2013. https://www.army.mil/article/97705/black_soldiers_in_the_revolutionary_war.

“James Armistead Lafayette.” American Battlefield Trust. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/james-armistead-lafayette.

“Lafayette’s Testimonial to James Armistead Lafayette.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-revolutionary-war/spying-and-espionage/american-spies-of-the-revolution/lafayettes-testimonial-to-james-armistead-lafayette/.

Morgan, Thad. “How an Enslaved Man-Turned-Spy Helped Secure Victory at the Battle of Yorktown.” History.com. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.history.com/news/battle-of-yorktown-slave-spy-james-armistead.

Nunnery, Jackie. “In Plain Sight: The Story of James Lafayette.” House & Home Magazine, August 12, 2019. http://thehouseandhomemagazine.com/culture/in-plain-sight-the-story-of-james-layfayette/.

“Pension application of James La Fayette (Fayette).” Pension records in the Library of Virginia. Accessed December 10, 2021. http://revwarapps.org/VAS807.pdf.

“Proclamation of Earl of Dunmore.” PBS, Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part2/2h42.html.

Quinn, Ruth. “James Armistead Lafayette, (1760-1832).” U.S. Army. February 21, 2014. https://www.army.mil/article/119280/james_armistead_lafayette_1760_1832.

Zielinski, Adam E. “Fighting For Freedom: African Americans Choose Sides During the American.” American Battlefield Trust. August 24, 2021. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/fighting-freedom-african-americans-during-american-revolution.

Additional Reading

“African American Service during the Revolution.” American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/african-american-service-during-revolution.

Black Patriots: Heroes of the Revolution. Directed by Jyllian Gunther. 2020; HISTORY Channel. https://watch.historyvault.com/specials/black-patriots-heroes-of-the-revolution.

King, LaGarrett J., and Jason Williamson. “The African Americans’ Revolution: Black Patriots, Black Founders, and the Concept of Interest Convergence.” Black History Bulletin 82, no. 1 (Spring 2019): 10-11. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5323/blachistbull.82.1.0010.

*exact birth and death dates are unknown. Listed dates referenced in Encyclopedia Virginia: https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/lafayette-james-ca-1748-1830/.