This Kurz and Allison print from 1890 depicts the moment of Col. Shaw’s death during the assault on Fort Wagner. Library of Congress

On July 18, 1863, a large force of Soldiers advanced in formation towards enemy fortifications outside of Charleston, South Carolina. As the sun set, the Confederate defenders opened fire on the 5,000-strong assault force. Sustaining casualties, the regiment pushed forward and scaled the fort parapet. They rushed to engage the enemy in fierce hand-to-hand combat. The commanding officer of the regiment, Col. Robert Gould Shaw, led his men and shouted “Forward, 54th!” before enemy fire struck him several times, mortally wounding him.

Formed on March 13, 1863 the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment served in the American Civil War. A unit of United States Colored Troops (USCT), the men of the 54th distinguished themselves as courageous Soldiers. Their gallant, yet failed, assault on Fort Wagner made them famous across the country. Their bravery inspired hundreds of thousands and proved that Black Soldiers could be as effective as white Soldiers.

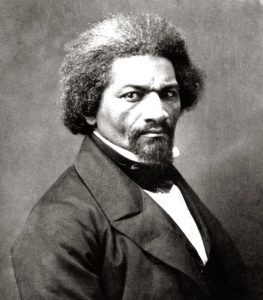

Many African Americans served in the Army and Navy in the early years of the country, but few remained by the time of the Civil War. As the Civil War began in April 1861, many abolitionists believed that free and formerly enslaved Black men should be allowed to join the Army. Frederick Douglass, one of the most influential abolitionists in the North and a former enslaved person, declared that, “…who would be free, themselves must strike the blow.” Yet many in the North were reluctant to give African Americans the opportunity to fight on behalf of the enslaved in the South.

Frederick Douglass helped recruit for the USCTs and two of his sons, Lewis and Charles, served in the 54th. His famous quote “Who would be free, themselves must strike the blow” was derived from his experience while enslaved. At 16 years old, he successfully fought and resisted being whipped by his enslaver. Douglass considered the incident the turning point of his life, stating “I was nothing before; I was a man now.” New York Historical Society

By 1862, President Abraham Lincoln believed that slavery should be abolished and that African Americans should have the opportunity to fight. After a Union victory at the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation granting all enslaved people in Confederate territory their freedom. The proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863, opening the door for African American service in the Union Army.

On January 26, 1863, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton ordered Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew to raise African American regiments. Andrew, an abolitionist, helped recruit the regiments alongside other Northern abolitionists like Douglass. Though the enlisted men were Black, the Army required officers to be white. Andrew selected Col. Robert Gould Shaw, the son of a prominent abolitionist family, to lead the 54th Massachusetts. Andrew chose Maj. Edward Needles Hallowell to serve as the regiment’s second in command after his older brother’s selection to command the 55th Massachusetts. Together, Shaw and Hallowell trained the men of the 54th. Recruitment for the regiment proved so popular that the 55th Massachusetts was formed to take on the excess recruits. After months of training, the 54th mustered into federal service on May 13, 1863. They deployed to Union-occupied Beaufort, South Carolina. There they joined another USCT regiment, the 2d South Carolina Volunteers. Together, the two units raided the town of Darien, Georgia. Shaw criticized the use of his men to pillage and burn rather than fight in battle. His men soon got their chance to prove themselves in combat.

This photograph of Col. Shaw was taken while he recruited for the 54th. Library of Congress

One of the main targets of the Union forces in South Carolina was the Confederate port city of Charleston. Union strategy in the Civil War included a blockade of the Confederate coast. Named the Anaconda Plan by Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott, the plan called for the taking of several Confederate coastal forts, including those protecting Charleston. In order to blockade and capture Charleston, Army and Navy forces had to capture the well-defended Fort Wagner.

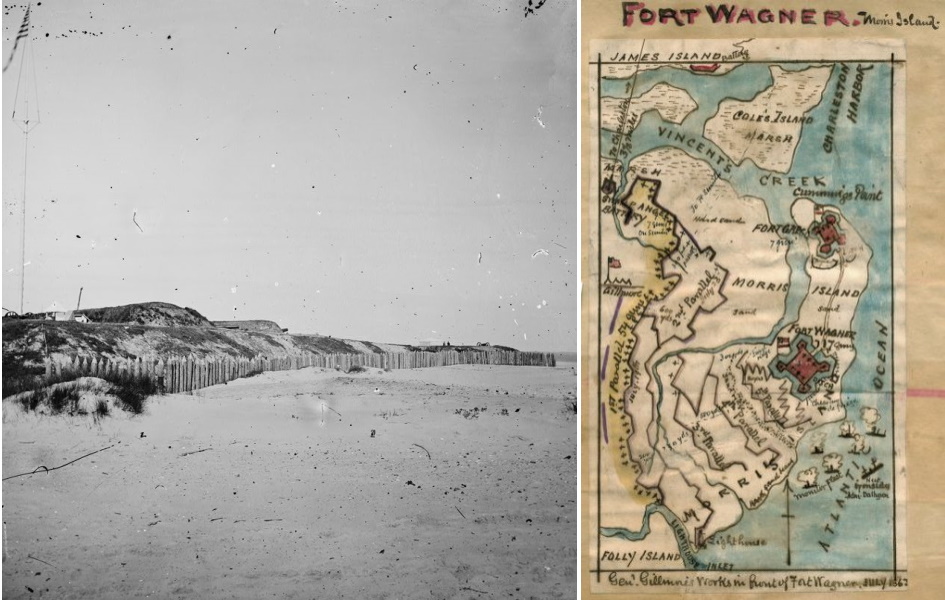

(left) Photographer Sam A. Cooley took this photo of Fort Wagner in 1865. Note the steep slope of the sand parapet and the wooden obstructions (abatis).This period map illustrates the defenses of Charleston, including Fort Wagner. (right) Note the Army siege lines and Navy ships. Library of Congress

Attempting to weaken the defenses of Fort Wagner, the Army seized nearby James Island. There, the 54th Massachusetts fought in their first battle, the Battle of Grimball’s Landing. Confederate general Johnson Hagood, one of the commanders of Charleston’s defenses, ordered the island re-taken. On July 16, 1863, a force of 3,000 Confederates attacked the 3,800 strong Union garrison on James Island. During the battle, 900 Confederates assaulted a position held by 250 men of the 54th Massachusetts. Although outnumbered, the men of the 54th held their ground and repelled the assault before Union forces retreated from James Island. In his official report on the action, Union Brig. Gen. Alfred H. Terry commended the 54th for their strong performance in battle, noting their “steadiness and soldierly conduct.”

As Union forces reorganized after the Battle of Grimball’s Landing, they planned for a renewed assault on Fort Wagner. On the morning of July 18, 1863, Union forces began to bombard Fort Wagner with fire from siege guns, mortars, and ships. During the bombardment, Brig. Gen. George C. Strong, commander of the attacking Union forces, visited Shaw and the 54th. He pointed to Fort Wagner and shouted to the assembled men, “Is there a man here who thinks himself unable to sleep in that fort tonight?” The men of the 54th loudly answered in unison “No!” Strong next asked as he gestured to the color bearer, “If this man should fall, who will lift the flag and carry it on?” Shaw answered, “I will” and the men of the 54th cheered.

Colors were American flags used by Civil War regiments. They were symbols of both national and unit pride. This color belonged to the 12th Infantry Regiment of the Corps d’Afrique and is on display in the National Museum of the United States Army. NMUSA

The geography surrounding Fort Wagner allowed only a few units at a time to attack. Strong gave Shaw and the 54th the place of honor as one of the leading regiments in the assault. After 11 hours of almost continuous bombardment, the men of the 54th advanced across a narrow beach towards the fort at around 7:45 p.m. As the Union bombardment ceased, the Confederate defenders left their shelter to man the parapets. The men of the 54th advanced across the sands with bayonets fixed. Shaw ordered his men into a jog and then into a charge as enemy forces opened fire. Many of the men fell, but their comrades pressed on to Fort Wagner.

Enemy fire killed Shaw as soon as he reached the top of the parapet. Undeterred, his men surged forward into the fort. They engaged the enemy in close range, hand-to-hand combat. Enemy musket fire from inside the fort killed and wounded hundreds. Hallowell¸ the color bearer, and Sgt. Maj. Lewis Douglass, the son of Frederick Douglass, were all wounded. As the battle raged on, Sgt. William Carney noticed the wounded color bearer. He dropped his musket and, despite multiple wounds, rushed forward and raised the colors as the chaos of the battle swirled around him. As elements of the 54th retreated, Carney declared, “Boys…the old flag never touched the ground.” Enraged by the sight of African American Soldiers, the enemy refused to take prisoners and executed the men of the 54th on the spot.

This image of Sgt. Carney bearing the 54th’s colors was taken in 1864. National Museum of African American History and Culture

Although they sustained heavy losses, the 54th pinned down the defenders, allowing other regiments to advance on Fort Wagner. They managed to enter the fort, though a Confederate counter-attack pushed out the remaining Union Soldiers. The attack on Fort Wagner failed, with the Union suffering horrific losses. 1,515 Soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured. The Confederates lost only 174 men. Confederate brigadier general William B. Taliaferro, commander of the defenders, wrote, “In front of the fort the scene of carnage is indescribable… I have never seen so many dead in the same space.” The 54th Massachusetts sustained the worst losses; almost half of the 600 men were killed, wounded, or captured, including Shaw. The Confederates buried Shaw in a mass grave with his men. They viewed this as the ultimate insult for a white man to be buried with African Americans. Shaw’s family felt differently; they believed it an honor that Shaw was buried in the field with his Soldiers.

This contemporary mural from the George F. Landegger collection dramatizes Shaw’s death during the assault on Fort Wagner. Library of Congress

The 54th spent several months recovering after the Fort Wagner debacle. Under the command of Hallowell, now a colonel, the 54th spent the rest of the war attached to various Union elements in the South. After Federal forces finally captured Fort Wagner on Sept. 6, 1863, Brig. Gen. Quincy A. Gillmore ordered an expedition to Florida to disrupt enemy operations. The 54th participated in this expedition and fought in the Battle of Olustee, the largest battle of the war to occur in Florida. After Confederate forces pushed back the main Union line, the 54th fought a successful rear-guard action which allowed the attacking force to retreat.

The 54th continued to operate in South Carolina, participating in the Battle of Honey Hill and the Battle of Boykin’s Mill. Yet, despite their valor and service, many refused to treat the men of the 54th equally. For the same service, the Army paid them less than their white counterparts and often overlooked them when awarding the Medal of Honor. After persistent efforts by Hallowell, Congress passed a bill on Sept. 28, 1864, which secured equal pay for all USCTs.

The men of 54th Massachusetts served courageously and honorably. Around ten percent of all Union Soldiers were USCTs and over 36,000 of them died during the war. Their service opened a door for future African Americans to join the Army, including the formation of the Buffalo Soldiers, a group African American cavalryman. Yet, recognition from the United States eluded some USCTs, including Carney. Although he received an honorable discharge, the Army never recognized him for his actions at Fort Wagner. On May 23, 1900, 37 years after the battle at Fort Wagner, Carney finally received the Medal of Honor for his gallantry in rescuing the 54th’s colors. Frederick Douglass and other abolitionists were proven correct, the 54th and other African American Soldiers contributed to victory in the Civil War.

This small fragment is all that is known to remain of the 54th’s colors from the assault on Fort Wagner. It is currently on display at the National Museum of the United States Army. NMUSA

A. J. Orlikoff

Lead Education Specialist

Sources

American Battlefield Trust. The 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. n.d. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/54th-massachusetts-infantry-regiment (accessed January 8, 2021).

—. The United States Colored Troops. n.d. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/united-states-colored-troops (accessed January 8, 2021).

Cox, Clinton. Undying Glory: The Story of the Massachusetts 54th Regiment. New York: Scholastic, 1991.

Dobak, William A. Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops, 1862-1867. Washington D.C. : Center of Military History, 2011.

Douglass, Frederick. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass: His Early Life as a Slave, His Escape from Bondage, and His Complete History to the Present Time. Boston: De Wolfe, Fiske & Company, 1892.

Egerton, Douglas R. Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments That Redeemed America. New York: Basic Books, 2016.

Linderman, Gerald F. Embattled Courage: The Experience of Combat in the American Civil War . New York: The Free Press, 1987.

Pohanka, Brian C. “Fort Wagner and the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.” American Battlefield Trust. n.d. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/fort-wagner-and-54th-massachusetts-volunteer-infantry (accessed January 12, 2021).

United States War Department. “The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies.” The Making of America. Cornell University Library. 2018. http://collections.library.cornell.edu/moa_new/waro.html (accessed January 8, 2021).

Winsboro, Irvin D. S. “Give Them Their Due: A Reassessment of African Americans and Union Military Service in Florida during the Civil War.” The Journal of African American History 92, no. 3 (2007): 327-46.

Additional Resources

Classroom and Research Materials:

American Battlefield Trust, “United States Colored Troops Collection.”

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/topics/united-states-colored-troops

American Civil War Museum, “United States Colored Troops.” https://acwm.org/learn/educator-resources/united-states-colored-troops/

Library of Congress, “Civil War Images: Depictions of African Americans in the War Effort.”

https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/civil-war-images-depictions-of-african-americans-in-the-war-effort/

Massachusetts Historical Society, “54th Massachusetts.”

http://www.masshist.org/online/54thregiment/index.php.

Public Broadcasting Service, “African-American Troops.”

https://virginia.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/african-american-troops-lesson-plan/ken-burns-the-civil-war/

Articles and Publications:

Gallagher, Gary W. Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollywood and Popular Art Shape What We Know About the Civil War. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Levin, Kevin M. “Why ‘Glory’ Still Resonates More Than Three Decades Later.” Smithsonian Magazine.

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/why-glory-still-resonates-more-three-decades-later-180975794/.

Videos:

American Battlefield Trust. “54th Massachusetts: The Civil War in Four Minutes.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I7isrEf-NXA&ab_channel=AmericanBattlefieldTrust.

Glory. Film by Edward Zwick. TriStar Picture. 1989