Albert D.J. Cashier, b. Jennie Hodgers

Private

Co. G, 95th Illinois Volunteer Infantry, 2nd Brigade, Sixth Division, XVII Corps, Army of the Tennessee

December 25, 1843 – October 10, 1915

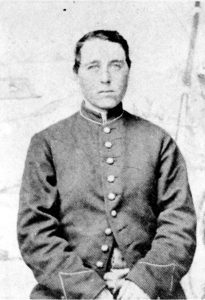

Albert D.J. Cashier, November 1864. Public domain

Albert Cashier, born Jennie Hodgers, served alongside the men of the 95th Illinois Volunteer Infantry with distinction throughout some of the fiercest fighting of the Civil War. While not alone as a woman serving on the battlefield during the war, Cashier retained his identity as a man throughout his later life, and was recognized as such by his comrades in arms and those surrounding him. How Cashier identified personally, as a woman or a transgender man, is unknown, but his desire to be known as a man, dedicated to service to his country in its most trying hour, is honored with masculine pronouns throughout this article.

Albert D.J. Cashier was born in Clogherhead, Ireland on Christmas Day, 1843. Cashier gave many varied stories of his early life and the manner in which he arrived in the United States, but the best accounts are pieced together from his brothers’ descendants and reports from his later years. Cashier spent his youth as a shepherd in Ireland before immigrating to New York as an adolescent. The demanding work of a rural shepherd shaped Cashier’s sense of identity and readied him for the hard life of a Soldier. Once in America, his mother married a man with the surname Cashier which Albert adopted for the rest of his life. He first started wearing men’s clothes to get work in a higher paying shoe factory, where he worked until his mother died sometime in the 1850s. After her death, Albert moved west, settling in Belvidere, Illinois as the Civil War began in 1861.

In 1862, following the bloody fighting near Shiloh, Tennessee, Cashier answered the call to duty alongside the other young men of Belvidere, and enlisted for three years in the 95th Illinois Infantry Regiment on August 6, 1862. The unit drilled in Illinois for two months before heading south to Cairo, Illinois and into rebel territory in November. By all accounts Cashier, only standing five feet tall on a slender frame, excelled as an infantryman, keeping pace on ruck marches and in digging trenches. While Cashier preferred to spend his time alone, he was well liked and accepted by his compatriots in the 95th, but it is unknown how many, if any, of his friends knew his true identity.

Cashier and the rest of the 95th soon found themselves in the thickest and fiercest fighting in the Western Theater of the Civil War. While serving in the XVI and later XVII Corps, the 95th participated in the Battles of Vicksburg in 1863, Brice’s Crossroads and Nashville in 1864, and Fort Blakely in 1865. The 95th then occupied Montgomery, Alabama until the end of the war. On Aug. 17, 1865, Cashier, alongside the rest of the 95th, mustered out with full honors at Camp Butler, in Springfield, Illinois. Throughout the war, Cashier and his unit served in almost 40 engagements and marched over 9,960 miles.

Throughout the war, many of Cashier’s fellow Soldiers attested to his grit, determination, and bravery. C.W. Ives, another infantryman in the regiment, told a story of Cashier that defies explanation. While cut off from the rest of their unit during a march through the South, Cashier identified and then taunted a Confederate force sent to capture the column. As the rebels took cover behind fallen logs, Cashier leaped up in full view and yelled “Hey you darn rebels, why don’t you get up where we can see you?” Another story, which remains unverifiable due to its very nature, states that when Cashier was captured during the Siege of Vicksburg, he overpowered his rebel captor, stole his weapon, and made his way back to Union lines. Whether these stories are true or not, their telling reflects the respect Cashier’s fellow Soldiers had for their comrade. His service, by all accounts, personified the courage the Union needed of its Soldiers to keep the United States together.

After the war, Cashier spent his life working odd jobs in and around Saunemin, Illinois. He worked first for the Cherbro family, then as a lamplighter and church janitor. Later, Cashier found work as a mechanic and driver for Illinois State Senator Ira Lish. One day in 1910, as Cashier inspected his vehicle, Lish climbed into the driver’s seat to assist and accidentally rolled the vehicle over Cashier’s leg, shattering it. Cashier never fully recovered from the wound and went to live at the Illinois Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home (now the Illinois Veterans Home at Quincy). There, several comrades of the 95th visited him, and he even entertained their commander for a day, while each dressed in their blue uniforms and traded old war stories. While the superintendent of the Soldier’s Home knew his identity, he kept Cashier’s biological sex a secret out of respect for all that he accomplished during the war.

Cashier developed dementia in his later years and he was transferred to a mental health hospital in 1913. There, the hospital attendees forced Cashier to dress in the attire of his biological birth against his wishes, and the national press soon became interested in his story. Unfortunately, his secrecy and dementia meant that very little became known of his remarkable story from Ireland, through Vicksburg, and into rural Illinois. Cashier died on Oct. 10, 1915 of an unknown infection. The Grand Army of the Republic, a Union veterans association, arranged his funeral with full military honors. He was buried in uniform, under a flag in the Sunnyslope Cemetery in Saunemin on Oct. 12, 1915.

Today, his home on the Cherbro property in Saunemin is a local tourist attraction run by the county historical society. The nature of Cashier’s birth, his desire to identify as a man, and his dedicated service to his country in that capacity speak across generations to the nature of military service. His service to the nation despite the secrecy of his identity is a poignant reminder that the nature of one’s birth has little impact on the nature of their patriotism.

Megan Willmes

Education Specialist

Jacob M. Henry

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Sources

“Albert Cashier Aka Jennie Hodgers.” American Battlefield Trust, February 26, 2019. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/albert-cashier.

Blanton, DeAnne, and Lauren M. Cook. They Fought Like Demons : Women Soldiers in the American Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2002.

Clausius, Gerhard P. “The Little Soldier of the 95th: Albert D. J. Cashier.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908-1984) 51, no. 4 (1958): 380-87. Accessed December 31, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40189639.

Grossman, Ron. “Flashback: Union Soldier Albert Cashier, Born a Woman, Fought Valiantly as a Man in the Civil War.” Chicago Tribune, August 29, 2019. https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-opinion-flashback-civil-war-soldier-gender-swap-cashier-20190829-tq5ff3enj5gkhdxdqqix5ji3uq-story.html.

“Jennie Hodgers, Aka Private Albert Cashier.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, August 14, 2017. https://www.nps.gov/articles/jennie-hodgers-aka-private-albert-cashier.htm.