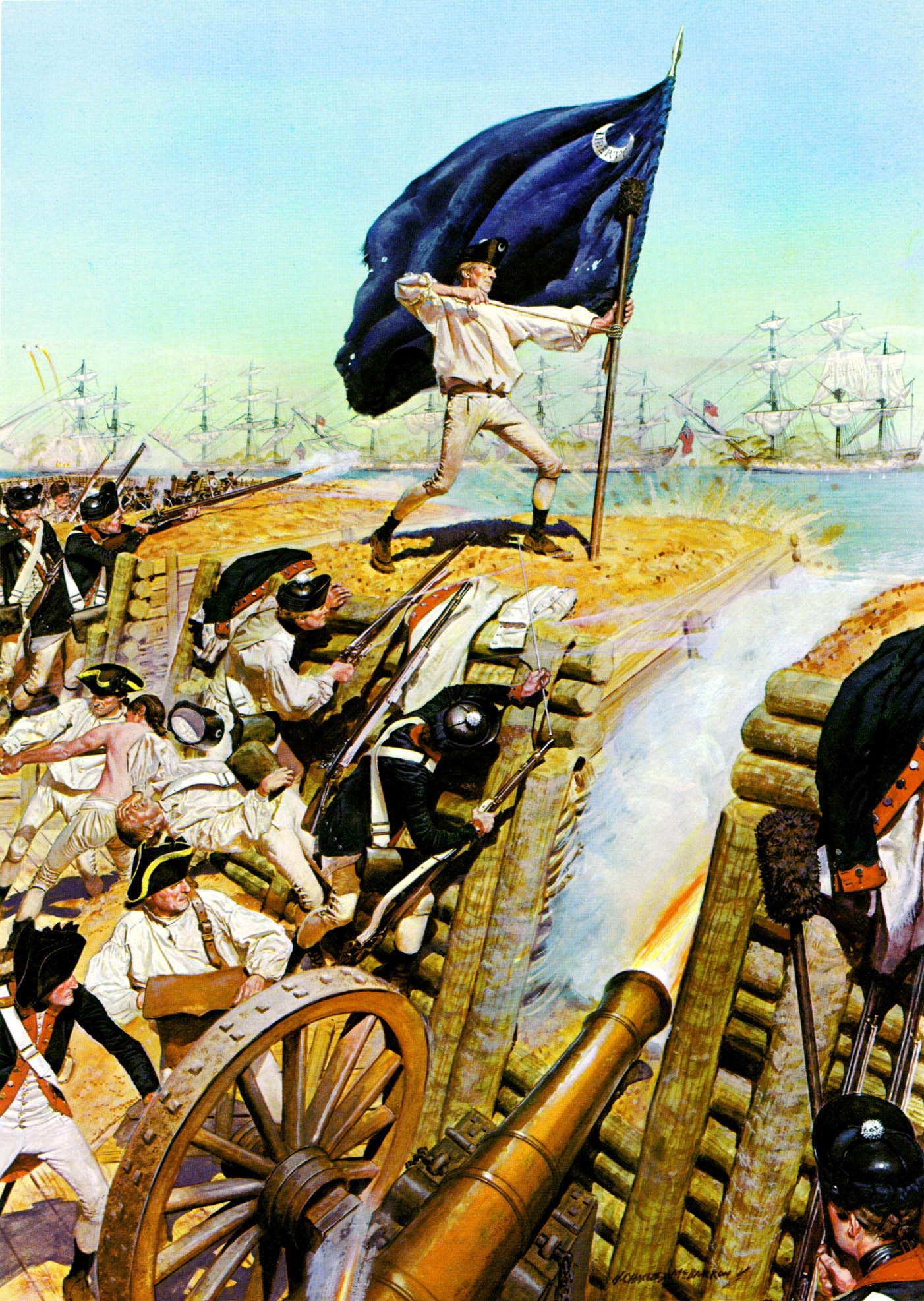

Expecting a British flotilla to attack Charleston at some point in early 1776, Colonel Moultrie supervised the building of a sand-and-log fort, sheltering 31 guns and its 344-man garrison, on Sullivan’s Island. General Lee thought the fort vulnerable to enemy fire and ground assault, and tried unsuccessfully to move its guns to the mainland. He did succeed in reinforcing the city, and having Col. William Thomson improve the Breach Inlet defenses. When the British navy attacked on 25 June, Lee thought it was “one of the most furious and incessant fires” he had experienced. Yet the American fort withstood the heaviest British shot, while the inexperienced but motivated American gun crews inflicted heavy damage on the enemy ships. When a stray British shot dropped the South Carolina state colors, Sgt.William Jasper braved the enemy fire to rig a temporary flagpole in view of the enemy fleet and the cheering American garrison. Colonel Thomson’s rangers meanwhile repulsed a landing attempt by Maj. Gen. Charles Cornwallis’ infantry at Breach Inlet on the eastern side of the island. American morale was boosted further by the arrival of General Lee with fresh gunpowder and reinforcements, while darkness ended the day’s fighting. Despite an estimated 7,000 cannon balls hitting the fort, the Americans lost only seventeen dead, twenty wounded, and a single ruptured cannon. The British lingered near Charleston long enough to repair their damaged ships before returning to New York City in late July and early August. The South Carolinian’s victory at Sullivan’s Island was the first to follow the American Declaration of Independence, and showed the British that more hard fighting would be necessary to subdue the American revolutionaries.

"On the morning of the 28th of June, I paid a visit to our advanced-guard...saw a number of the enemy’s boats in motion...as if they intended a descent upon our advanced post...I immediately ordered the long roll to beat, and officers and men to their posts. We had scarcely manned our guns, when the following ships of war came sailing up, as if in confidence of victory...we began to fire; they were soon abreast of the fort, let go their anchors, with springs upon their cables, and begun their attack most furiously...General Lee paid us a visit through a heavy line of fire, and pointed two or three guns himself; then said to me, ‘Colonel, I see you are doing very well here, you have no occasion for me, I will go up to town again,’ and then left us. Never did men fight more bravely, and never were more cool; their only distress was the want of powder . . . there cannot be a doubt, but that if we had had as much powder as we could have expended in the time, the men-of-war must have struck their colors, or . . . have been sunk, because they could not retreat...It being a very hot day, we were served along the platform with grog in fire buckets, which we partook of very heartily...After some time our flag was shot away...Sergeant Jasper perceiving the flag...had fallen without the fort, jumped from one of the embrasures, and brought it up through a heavy fire, fixed it upon a spunge-staff, and planted it upon the ramparts again; Our flag once more waving in the air, revived the drooping spirits of our friends...till night had closed the scene."

Col. William Moultrie

Sources

Col. William Moultrie, commander of the Charleston

garrison. “Memoirs of the American Revolution.” pp. 174–80.

www.founders.archives.gov