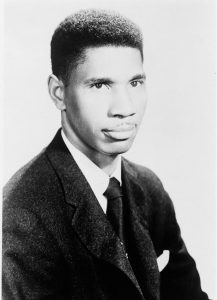

Medgar W. Evers

Technician Fifth Grade

325th Port Company

July 2, 1925 – June 12, 1963

Medgar W. Evers Library of Congress

Famous activist, Soldier, and family man Medgar W. Evers was one of the most effective civil rights advocates in Jim Crow Mississippi. He fought for voting rights and desegregation and investigated the murder of 14-year old Emmet Till. His courage in the face of violence and political deadlock inspired countless activists across the country.

Born on July 2, 1925, in Decatur, Mississippi, Medgar Wiley Evers grew up surrounded by racial oppression. African Americans in Jim Crow Mississippi were denied access to many public and private facilities available to white Mississippians. African Americans had no choice but to go to separate, underfunded schools. The state government passed laws that denied African Americans the vote through high poll taxes and literacy requirements. Mississippi also banned interracial dating and marriage. Vigilante violence was a common method used to enforce these strict laws.

Evers’ father was a farmer and his mother was a housewife. As the third of five children, Evers looked up to his older brother, Charles, and worked with him for much of his life. His segregated high school was 12 miles away from his house, and Evers had to walk there and back each school day. At age 11 or 12, Evers witnessed the lynching of Willie Tingle, a family friend. His route to school passed the location where Tingle was hanged.

In 1943, Evers dropped out of high school and enlisted in the Army Reserve Corps during World War II. Serving in the U.S. Army changed Evers’ life. At the time, the Army segregated Black and white troops and relegated African Americans to non-combat roles. He unloaded weapons, vehicles, and supplies from transport ships. After D-Day, Evers and his 325th Port Company went into France, where he served in the all-Black 3677th Quartermaster Company and 958th Quartermaster Service Company. He was part of the Red Ball Express, a truck convoy system primarily composed of African American Soldiers that supplied Allied forces.

Europe had no racist Jim Crow system and was comparatively more accepting of African Americans than the United States. Military service also helped African American Soldiers gain new skills and confidence in fighting for their rights. Evers pledged that when he returned home, he would fight for change. Evers said to his brother, who also served at the same time, “When we get out of the Army, we’re going to straighten this thing out!”

After receiving an honorable discharge from the Army in 1945, he and Charles returned home to Decatur. The path to political representation there was difficult and dangerous. In 1946, as the brothers attempted to register to vote at the Decatur courthouse, local white residents hurled racial slurs at them. Government officials prevented them from registering. The brothers recruited a group of four other African American veterans to come with them a second time to the courthouse on July 2, 1946. Charles carried a .38 caliber pistol for self-defense, while several local men carrying shotguns stood outside to intimidate them. The Evers brothers once again left without voting. Violence and intimidation of African Americans was a fact of life in Jim Crow Mississippi.

Evers completed high school after his service in the Army. Medgar and Charles then went to Mississippi’s Alcorn College (now Alcorn State University). Evers earned a degree in business administration while Charles earned a degree in social studies. While there, Medgar met his future wife, Myrlie Beasley. They married on Dec. 24, 1951. After receiving his degree, the couple moved to Mound Bayou, Mississippi. He worked as an insurance salesman in the Magnolia Mutual Life Insurance Company. While working as an insurance salesman, Evers witnessed an attack on an African American in Union, Mississippi. He was infuriated by the fact that white supremacy was still dominant in Mississippi, and he decided to act on it.

Many public universities barred African Americans from attending, and Evers worked to change that. He applied to the University of Mississippi’s law school in 1954 soon after the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision desegregated public schools. Despite the fact that schools could not bar a student based on race, the university denied Evers entry. He joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to help the organization’s campaign to desegregate the University of Mississippi. One of the oldest civil rights organizations in the country, the NAACP sought to secure the rights of minority groups and uphold equality under the law. As NAACP Mississippi field secretary between 1954 and 1963, he began the work that he became known for: organizing local chapters of the NAACP and investigating violent crimes against African Americans. He also organized voter registration drives and led protests to desegregate public buildings. Evers worked tirelessly to force the University of Mississippi to follow the law and admit its first African American student, James Meredith, in 1962. This became a major moment in the civil rights movement and thousands of angry white pro-segregationists rioted in response. Evers’ work was dangerous, but he knew he had to continue fighting for change. Civil rights leaders across the country applauded his efforts, and he became one of the most well known activists in Mississippi.

Evers inspired a generation of civil rights activists in Mississippi and across the country. As part of the NAACP, he developed connections between chapters by driving across the state, traveling 42,769 miles in his Oldsmobile in three years. Evers had the remarkable talent to transform a person’s fear into concerted action. He built a dedicated group of activists who made significant progress to ensure African American voting rights in Mississippi, despite threats of violence that caused many to leave the states’ civil rights organizations during the 1950s and 60s. Mississippi activists and many others put grassroots pressure on Congress leading to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

On June 12, 1963, Evers was assassinated around midnight while returning home from work. Byron De La Beckwith, the assassin, was a member of the Ku Klux Klan and White Citizens Council. Two all-white juries failed to convict De La Beckwith. Three thousand people attended Evers’ funeral in Jackson, Mississippi. Civil rights activists considered him a martyr for the cause. His death shook the country and many activists demanded action. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August 1963 was in part fueled by anger over Evers’ assassination. Rachelle Horowitz, aide to one of the March on Washington’s primary organizers, said, “Originally it was conceived of as a march for jobs, but as ’63 progressed, with the Birmingham demonstrations, the assassination of Medgar Evers and the introduction of the Civil Rights Act by President Kennedy, it became clear that it had to be a march for jobs and freedom.” One year after his death, and on Evers’ birthday, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Many consider his death a pivotal moment in the Civil Rights movement.

Evers was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors on June 19, 1963. The NAACP posthumously awarded Evers the Spingarn Medal, the organization’s highest honor. The City University of New York named their new Brooklyn campus Medgar Evers College in 1970. Myrlie Evers-Williams, Medgar’s wife, continued the struggle for equality and became the first chairwoman of the NAACP in 1995. Charles Evers took his brother’s position as Mississippi NAACP field director in 1963 after Medgar’s death and had a long career in politics and civil rights activism. After many calls to bring De La Beckwith to justice, he was retried and convicted of Medgar Evers’ murder in 1994. Medgar Evers once said, “You can kill a man, but you can’t kill an idea.” A hateful act of violence cut Evers’ life short, but his fight for justice and equality continued long after his death.

Jordan Ginder

Graduate Historic Research Intern

Sources

Bamford, Tyler. “Medgar Evers: US Army Veteran and Civil Rights Leader.” The National World War II Museum. February 22, 2021. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/medgar-evers-us-army-veteran-and-civil-rights-leader.

Bell, T. Anthony. “Army Veteran Medgar Wiley Evers a Foot Soldier in Struggle for Justice.” U.S. Army. February 25, 2020. https://www.army.mil/article/233093/army_veteran_medgar_wiley_evers_a_foot_soldier_in_struggle_for_justice.

“Black Veterans Return from World War II.” SNCC Digital Gateway. SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University, September 23, 2021. https://snccdigital.org/events/black-veterans-return-from-world-war-ii/.

Blakemore, Erin. “How the Assassination of Medgar Evers Galvanized the Civil Rights Movement.” National Geographic, June 12, 2020. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/medgar-evers-assassination-galvanized-civil-rights-movement.

“Evers, Charles.” Mississippi Civil Rights Project. Accessed October 29, 2021. https://mscivilrightsproject.org/newton/person-newton/charles-evers/.

“Evers, Medgar.” Mississippi Civil Rights Project. Accessed October 29, 2021. https://mscivilrightsproject.org/newton/person-newton/medgar-evers/.

“Evers, Medgar Wiley.” The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute, Stanford University. May 21, 2018. https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/evers-medgar-wiley.

Fletcher, Michael. “An Oral History of the March on Washington.” Smithsonian Magazine, July 1, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/oral-history-march-washington-180953863/.

Jackson, David. “Segregation.” Mississippi Encyclopedia. Center for Study of Southern Culture, April 15, 2018. https://mississippiencyclopedia.org/entries/segregation/.

“Life of Medgar Evers.” Medgar Evers College, City University of New York. Accessed October 29, 2021. https://www.mec.cuny.edu/history/life-of-medgar-evers/.

Levy, Marc. “Medgar Evers.” Medic in the Green Time. Accessed November 13, 2021. https://medicinthegreentime.com/medgar-evers/.

Sina. “Medgar Wiley Evers.” The MY HERO Project. April 22, 2019. https://myhero.com/Evers_NW.

Sturkey, William. “Medgar Evers’s Legacy of Organizing in Mississippi.” Black Perspective (blog), April 15, 2019. https://www.aaihs.org/medgar-everss-legacy-of-organizing-in-mississippi/.

Davis, Jennifer. “Medgar Evers: A Hero in Life and Death.” Library of Congress Blog, July 7, 2021. https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2021/07/medgar-evers-a-hero-in-life-and-death/.

Williams, Michael Vinson. Medgar Evers: Mississippi Martyr. University of Arkansas Press, 2011.

Additional Resources

Marable, Manning. The Autobiography of Medgar Evers: A Hero’s Life and Legacy Revealed Through His Writings, Letters and Speeches. Edited by Myrlie Evers-Williams. Washington, DC: Perseus Books, 2005.